Eulogy for Cliff Robinson

It was a shock for me when Laila Harré called me to tell me Cliff had passed away that Sunday evening – though given his age and his long battles with health it shouldn’t have. I had planned to travel down to Thames to see Cliff the next day. The evening before I spoke to him on the phone and he told me he would be in hospital for 8 days – on the basis of which despite him being so obviously weak and struggling, I was happy to reassure myself he’d come through again.

I have known Cliff Robinson for just under 40 years. In recent years we talked frequently by phone, over the last year every 3 or 4 days or so. In April last year Cliff asked me to help him write his autobiography. I had been suggesting he do this for some years so I was more than happy to help.

In May, the first chapter – actually the introduction, a rather dramatic one too – about the day in June 1970 his wife Mary left him, and the children Marita and Johnny – came through. It was followed by 11 chapters at regular intervals. These were sent as emails, containing densely packed text of varying fonts, sometimes italicised, sometimes not. There was no punctuation – not even full stops. While disconcerting at first sight – despite the appearance, these proved to be coherently constructed chapters of well written prose with a sentence rhythm which made punctation easy. What’s more they were highly readable. All I had to do was copy the email to a word document, standardise the font, increase the line space to 1.5, justify the text, insert the full stops and other bits of punctation – and with the odd highlighted suggestion send it back. Cliff was very happy with them.

Cliff proved to be talented storyteller and his book promised to be important piece of NZ social and political history. Unfortunately he only got as far as 1970 – and so does not include his politically important time in the Alliance. Cliff was so enthusiastic about his book project, that I was foolishly confident that nothing would stop him from finishing it. I was wrong – hence my shock – as well as my grief.

In this tribute to Cliff I will quote from his manuscript here and there in recounting parts of his early life.

As his nephew James Turner has mentioned Cliff Robinson was born in Onehunga in 1936, into a family which just returned from a Great Depression work camp – an experience that marked the family deeply, the hardships and humiliations Cliff heard about, his mother lost two children there, especially from his beloved older step-sister Ida. The Depression work camp had a formative influence on Cliff’s life philosophy.

Cliff was descended from good people, 19th century pioneers, from England, Scotland, Ireland and Australia. On his father’s side, his grandfather John Robinson, a veteran of the NZ Wars, had settled at Thames where he and his grandmother ran a bakery. In the early 20th century the family moved to Onehunga, where grandfather Robinson became involved in local government, serving two terms on the Onehunga Borough Council. His mother’s family, the Couch’s also came from Onehunga – [as indeed did my own mother]. Cliff’s father James was the youngest of 13 children.

Cliff grew up during the Second World War retaining clear memories of US marines training in the then open fields around Te Papapa School where they rehearsed assaults on Japanese held islands in the Pacific. He wrote:

‘I had a wonderful childhood in Onehunga. At Te Papapa school I was neither top of the class or at the bottom. I had plenty of mates which was very important. We always had plenty of good fresh food which father grew in a huge garden. We had chooks and ducks. Mum was a wonderful cook and a great homemaker as well as being a great knitter – she made all our clothes. So we always had great warm jerseys to wear.’

An influential person in his young life was his grandmother, his mum’s mother. She was an Australian born on the goldfields of Ballarat, in the 19th century. His Nana, as he called her lived close by Cliff’s parents and as a little boy Cliff would stay overnight with her and sleep in her bed. His chapter on his grandmother is one of the most affecting parts of his story.

In recalling her death in 1954 Cliff wrote:

‘She had lived in New Zealand for over 60 years but never learned to say chance and dance like a kiwi. Nana was a fervent supporter of the first Labour government and very proud of the influence that a number of her fellow Australians had on that wonderful government. It is now 65 years since Nana died. I have never forgotten that wonderful woman and the influence she had on my life.’

But the highlight of his boyhood was the long summers spent in the family bach at Kawakawa Bay.

Cliff recalled:

‘My father was a labourer all his life. A good man with a liking for the drink. Despite his lowly occupation we never wanted for anything. We always had a car and what’s more a bach at Kawakawa Bay. When working for the Americans, Dad saved up 50 Pounds to buy a section in a part of Kawakawa Bay. Here he built a bach. Two rooms, one for sleeping the other for cooking and eating. No electricity or phone. No floor coverings. Cooking was done on a woodburner stove. Pretty basic but for me it was paradise.’

The long summer days were spent with his mum and sister Verna were filled with swimming and fishing and playing in the bush.

‘Our days were always full, so tuckered-out from our adventures we would go to bed early, and listen to the haunting calls of the ruru before nodding off.’

Then came the end of the Golden Weather.

‘One day when I was 15 and out fishing with my father he told me he had sold the bach. I was absolutely devastated.’

Cliff was good at sports, especially rugby and tennis playing in an Auckland championship rugby team twice, and representing Auckland once In tennis. He was the tennis club champion in doubles and mixed doubles. Rugby trips at the end of the season were a major highlight for him.

He recalled:

‘I had my first drink on a rugby trip. I felt like a million dollars from the very first beer I had, but for me this was also the beginning of a long battle with the bottle.’

In 1952 he left school and was apprenticed as a fitter to the NZ Railway Workshops at Otahuhu. This is where Cliff first became active in trade union and left-wing politics. Cliff referred to it as the ‘working class university of south Auckland.

‘It was really exciting to go along to union meetings which were held at lunch time to listen to the debates, to learn trade union history and to feel part of the movement of the working class.’

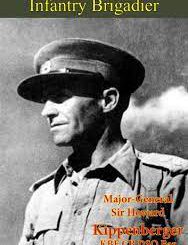

The union insured that the workshops had a well-stocked library. It was here Cliff picked up a book which was to have a profound influence on his political thinking.

‘I remember picking up a biography of the surgeon Norman Bethune. Never had I, before or since, been so inspired. A Canadian from the privileged class, he worked amongst the poor unable to afford medical treatment during the Great Depression. Bethune volunteered to serve with the republican forces in the Spanish Civil War. He then went to China to establish a medical unit alongside the communist forces of Mao Tse Tung, fighting a civil war with the nationalist forces of Chiang Kai Shek. Bethune contracted tetanus and tragically died in the 1940s.’

From his late friend Tom Newnham, Cliff also learned of a New Zealand woman, relatively unknown in her native country but famous in China. She an assistant of Dr Bethune, for whom Cliff was also to have a lifelong admiration.

‘Her name was Katherine Hall who was a missionary in China who had worked tirelessly as a Nurse alongside Dr Bethune. Rewi Allan said that had she had been a man she would have been famous. Bethune wrote in his dairy. ‘I have met an angel.’ The Chinese called her He Mingqing (Clear, Bright, Earnest).’

Cliff then was called up to national service. He enjoyed army life but he had read enough in the railway workshops library to openly challenge the scare stories put into the young servicemen about the coming Red Chinese ‘yellow peril’. Cliff rejected the anti-China propaganda of the first cold war which we should remember led to the dreadful Vietnam War and to the pointless loss of life of 3 million people, just as he rejected the latest version of anti-Chinese propaganda, emanating from Washington and Canberra, particularly over the last couple of years or so.

It was at the railway workshops in the mind 1950s he met a man who was to play a formative part in his political life, Ray Gough one of the most respected tradesmen in the workshops. Cliff spoke at Ray Gough’s funeral early last year. It was through Ray Gough that Cliff joined the Communist Party of New Zealand and was active in the party for several years, though he still kept up his involvement in sport.

In 1958 Cliff transferred from the Railway Works at Otahuhu to the new diesel depot at Parnell (only demolished in 2016). It was working at Parnell which awakened in him his life-long wanderlust – his zest for travel.

‘Some of the tradesman at the Parnell depot had been marine engineers. I listened in awe to their seagoing experiences. I used to catch the suburban bus in Te Papapa which snaked its way through One Tree Hill, Newmarket then down Anzac Ave where I would get off to walk down the hill behind the Station Hotel to the Strand. This was one Monday morning in 1958. I kept thinking of the stories from the ex marine engineers, so instead of heading up the Parnell Rise to the diesel depot I took a left turn at the Strand and headed for Quay Street – to the Union Steamship Company office. ‘I am looking for a job as a junior engineer’, said I. ‘Do you have your apprenticeship papers?’ I was asked. ‘No. But I can get them for you.’ ‘Would you be prepared to sail to Singapore this Friday?’ ‘Of course’ said I.’

Cliff signed on the Union Company’s Wairata as the 5th engineer (a ‘fiver’ as they were called) and sailed on the ‘Far East’ run, trading from Auckland to Cairns, Singapore, Port Swettenham (Kuala Lumpur) , Columbo, Trincomalee and Calcutta.

Cliff then shipped out in British ships on the trans-Atlantic run. From time to time his political past opened him up to persecution mainly from the US authorities who wouldn’t let him off the ship when visiting the States.

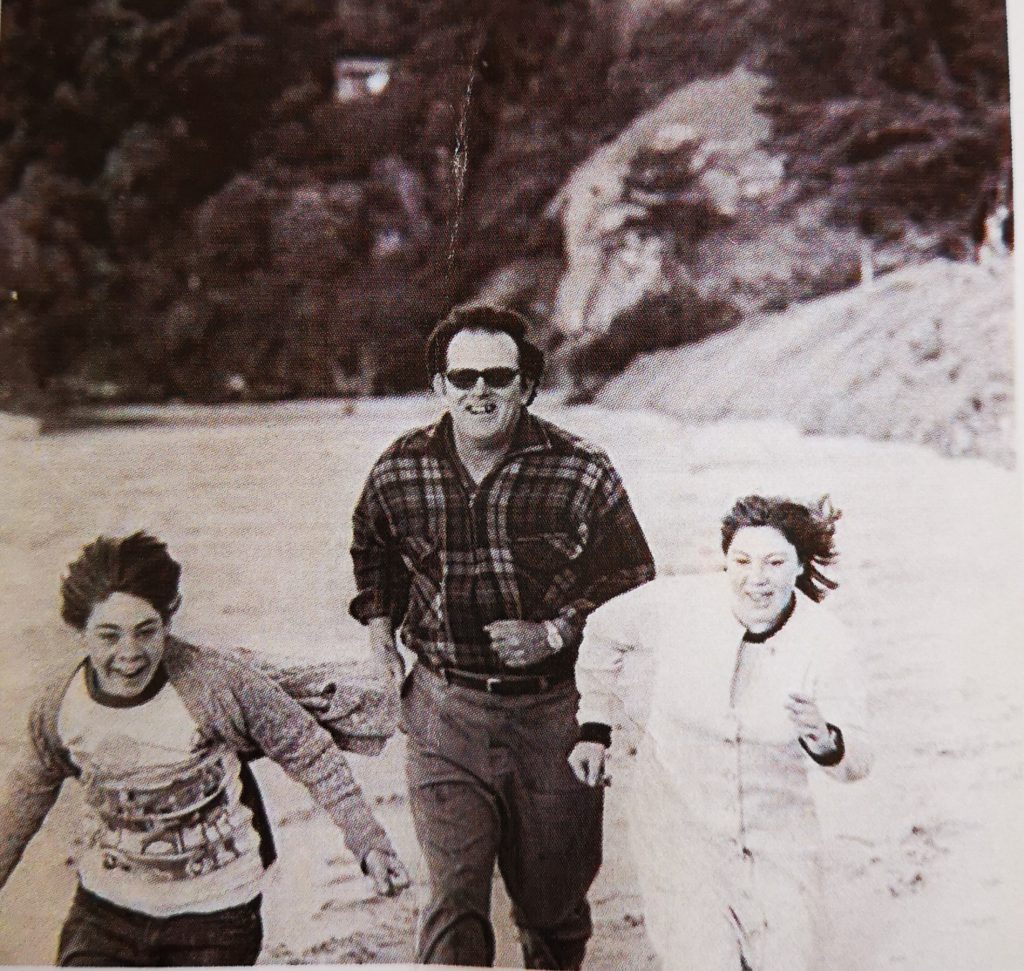

He was living in the UK in 1966 when he met and married his wife Mary. Returning to New Zealand in 1967, the couple had two children Marita in 1967 and John in 1969. Unfortunately, both children were intellectually disabled – an enormous blow for the young couple. The marriage effectively ended on 5th June 1970 when Mary unable to cope with the children left early one morning without warning. This was a huge blow for Cliff, and one gets the impression this great crisis tested him to the limits – as indeed it would anyone. But this was where his strength of character – and his essential goodness as a person – came to the fore.

In the wake of the break-up of his marriage, Cliff made two life changing decisions. He would not send his babies to an institution; and he would give up drinking. Two commitments he honoured to the end of his life.

Thus, also began Cliff’s protracted battle with the authorities for a better deal for the intellectually handicapped and their parent carers.

In 1980 the family moved to Waiheke Island, with Cliff committing to look after another disabled boy Tony. I first met Cliff in 1983 when he stood as a candidate for the Waiheke County council.

I was the chair of the local Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society branch at the time and Cliff who had a lifelong love of New Zealand native forests and wildlife, became active in our conservation campaigns. Cliff was a leading volunteer in the work to replant the Tiritiri Matangi island open sanctuary, which was began by Waiheke Forest & Bird in May 1984. Apart from the regular branch trips, Cliff and two or three dedicated volunteers would go to Tiri to work there for several days planting trees. At Tiri he became a good friend of the island ranger, former lighthouse keeper Ray Walter and his wife Barbara. And It was through Forest & Bird that Cliff & I became friends. When Cliff stood for the county council again in 1986 I was his chief helper. I was to help him in one way or another in nearly all his subsequent political campaigns thereafter.

Cliff moved back to the city, to Kelston in early 1989, where he nursed his ailing mother Verna until she passed away aged 89.

In 1989 he joined Jim Anderton’s New Labour Party to join the fight to stop the sellout of our country. He was the NLP parliamentary candidate for Auckland Central in the 1990 general election. Following the formation of the Alliance in late 1991 he became a stalwart for the party and a major fundraiser, through his popular housie evenings, standing for parliament several times in the New Lynn electorate. Though his barn-storming style always resonated with audiences, it was never enough to displace the incumbent, veteran Labour MP Jonathan Hunt.

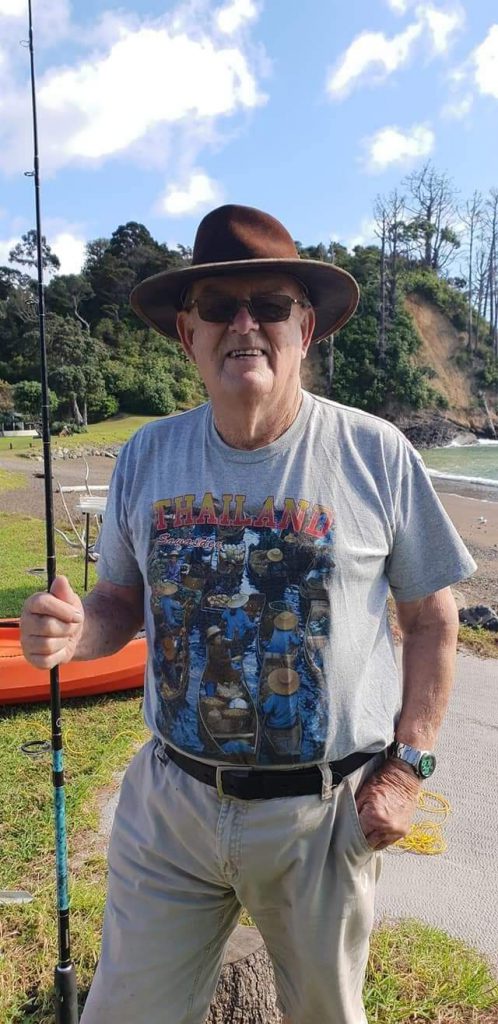

In the late 1990s withdrawing from active politics, Cliff, with Marita and John, moved to the peaceful haven of Ruamahanga Bay, north of Thames, to grow vegetables and pursue his lifetime love of fishing and to travel – always with the children.

But here he was soon drawn into an environmental battle, leading a successful public campaign in 2005 to persuade the then Transit-NZ (now NZTA) to abandon plans to cut down dozens of iconic Pohutukawa trees along coastal State Highway 25. The chairman of Transit David Stubbs listened and the trees were saved and for that Cliff always greatly respected the man.

Cliff was also the leader along with Peter Humphries, the mainstays in a prolonged legal action on behalf of hundreds of parents of severely disabled children from 2002 to 2012 against the Ministries of Social Development, Health and the Office of Crown Law. The plaintiffs won every case with the Court of Appeal upholding the decisions in the parents’ favour. Unfortunately, the then National government introduced retrospective legislation which effectively nullified the Court of Appeal decision.

Though robbed of victory Cliff’s tireless work won widespread respect and admiration from his fellow parents, human rights officials like Roslyn Noonan and lawyers associated with the proceedings on both sides especially Frances Joychild of the Human Rights Commission. It was for this work he was honoured in 2012 as the ‘Waikato person of the year’.

Cliff had so many friends and relatives, you must forgive me if I overlook a name in the limited time I have. But first of all I know it was an enormous comfort to him to have the help and support of the Hon Laila Harré and her husband Barry. It was especially reassuring for Cliff in his last months to know that Laila would be there to keep an eye on Marita and John, Then there was Ron & Jo Cavaney, Eric Rikkerink, Len Richards, Maxine Gay, Jim Bennett, Robert Reid and former MP Keith Locke. Over here at the Coromandel here saw a lot of Harry Parke, and the late Hon Jeanette Fitzsimmons, his mate Ken Carpenter and former Green MP Catherine Delahunty.

Early last November, only a few weeks ago, My wife Jenny and I called to see Cliff at Ruamahanga Bay. He was with Marita. Though he looked somewhat pale he struck me as happy and at peace with himself. I was impressed with what he had done with the house, adding another storey on – with ample space for his paintings and ornaments, inherited from his family, from his time at sea and souvenirs of his later travels. He made us cup of tea, Marita served biscuits and we had a good chat. It was a very happy day for us. I came away with a feeling of serenity and comfort from that home, the solidity of which and the marvellous mementoes reassured me that Cliff would be around for quite few more years to come. We agreed that he and Marita would come to stay on Waiheke next February to enable us to work on the book together. But it was not to be.

How to sum up Cliff.

Cliff Robinson was fundamentally always a political man, though he had decades before moved on from the Communist Party and was indeed critical of it, he always remained convinced of the non sustainability of capitalism – and remained a staunch critic of capitalism’s waste, greed, injustices and wars. He was a class conscious member of the working class – a class fighter. Cliff retained a burning belief in a future socialist world, of economic justice and peace, of a fair go for everyone. And in living his life he tried to practice what he preached.

And his life?

Cliff’s life was indeed a life of service. Of selfless dedication and love. Love for his children, for his family, for the natural world – and for his fellow man. A life therefore of goodness and we thus can take some comfort in our grief and sense of loss knowing that Cliff Robinson lived a good life.

Tragically Cliff was unable to finish his book, but rather perhaps like NZ railway workshop engineers we can arc-weld and bolt on material from his papers, from his letters and speeches, with perhaps contributions of essays from the people who worked with him in his many campaigns and this finish the job.

I will close with the words of the German socialist playwright Bertold Brecht which I think apply very much to Cliff Robinson and his life.

‘So this is it, but its not enough. But at least it will tell you that we are still here. We are like the man who carried with him a brick to show the world what his house was like.’

Thankyou for this wonderful account of Cliff’s life. We were close friends of Cliff, Marita and John.

Thanks Carolyn,

Please excuse my slow response. I havent checked my website for months!!! Cliff and I used to talk on the phone regularly, sometimes several times a week.

His loss is irreparable for me.

My thanks and in sorrow,

Mike

What a beautiful eulogy to an incredible man. Every life has a story. I saw the YouTube video of Cliff and the kids a few years ago and I just watched it again today because I remember how awesome Cliff was and I wanted to see it again. I was so sorry to read in the comments that Cliff had passed away. In America and New Zealand there is little to no help for caretakers without a huge amount of money being spent. When you have chronically/acutely ill family members here they have ‘respite’ care in nursing homes but only the rich can afford it. I know Laila will fight for proper care for Maurita and Johnny. You were obviously a very good friend to Cliff and the kids and he must have looked forward to his conversations and visits with you greatly. Much love from the United States.

Thanks very much Beth for the kind words,

May apologies for being slow to reply. When did you meet Cliff? And how long have you lived in the USA. As you know Cliff and I talked on the phone sometimes several times a week. I would love to ring him up now. My thanks and in sorrow,

Mike

Very sad to see Cliff has passed away…What a lovely man and wonderful father and a true kiwi battler.

My condolences to his beloved children, Johnny and Marita.

Rest peacefully Cliff – you did good.

Thanks Kim.