A weekend in Brittany

On Thursday evening, 27 June at about 5.40pm, after another marathon meeting of the council’s governing body, where I had anxiously waited to cast my vote against the so-called ‘Future Fund’ (because it means the privatisation of the last of the publicly owned shares in Auckland International Airport), I barrelled out of the Town Hall and into the winter darkness. Stashing my winter overcoat and brief case in my office at 135 Albert Street, I made a dash for the 30 bus to Manukau Road to rendezvous with wife Jenny who was waiting with daughter-in-law Ivy who was to drive us to the airport. Happily we made it on time. Fastening our safety belts for the flight to Shanghai, I felt a sense of relief to be getting away.

After a long 30 hour flight across the world including a 6 hour stopover at Shanghai-Pudong, Jenny and I arrived at Paris-Charles de Gaulle, to find it was a cheerful summer’s evening – and a Friday night too! Catching the RER train past the soon-to-be-busy Stade de France, we bought a bunch of Metro tickets at Châtelet-Les Halles and transferred to the Mairie D’Issy line for Montparnasse. Our little hotel wasn’t too far to walk and handy to lots of affordable bistros and restaurants which are such a great feature of Paris. Our room was tiny but it was a luxury to sleep in a bed at last. Early next morning, still rather jet-lagged, (‘Travel is not a holiday’) we made a dash for the Gare Montparnasse train station and the Grande Lignes, boarding the high speed TGV for Brest along with a crowd of city weekenders. We were going to stay with old friends that we hadn’t actually met. Philippe Huon de Kermadec retired medical doctor, and Jean-Pierre Boin naval commander (retd.), have been long time correspondents. Researchers of the history French navy, especially at the time of the Great Revolution, they generously provided me valuable information for my book ‘Navigators & Naturalists.’ I had originally intended to meet them in 2021 but the pandemic put a stop to that.

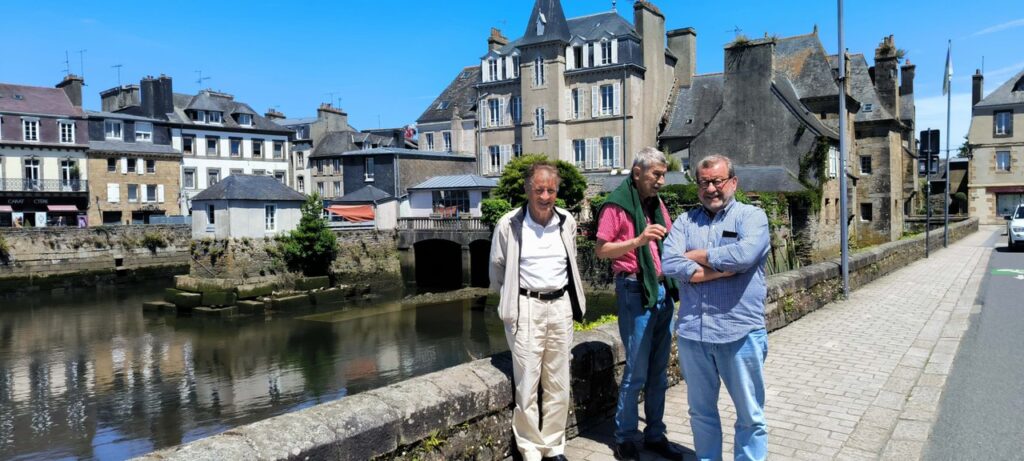

By prior arrangement, Jean-Pierre was waiting at Morlaux station. After introductions he drove us to the medieval town of Landerneau some 15 km from Brest where his old friend Philippe Huon de Kermadec awaited.

If the name Kermadec seems familiar, yes, it was his great, great, great etc., uncle, Jean-Michel Kermadec, page boy to King Louis XV, (along with his older brother, another naval officer, Philippe’s ancestor Jean-Marie), a decorated naval officer in the American War of Independence, Knight of St Louis, scholar and Pacific explorer, after whom the Kermadec Islands, the most northern territory of New Zealand, are named. Jean-Michel is honoured with a remarkable number of place names, the Huon Valley and Huon River in Tasmania, the Huon Peninsula and Huon Gulf in New Guinea, the undersea Kermadec Ridge of some 40 volcanoes and the Kermadec Trench one of the planet’s deepest. Finally because of their association with the Kermadec islands a veritable host of biota, invertebrates, plants and birds, in both common and scientific names bear variations of the Breton name Kermadec.

After lunch and a walk around of picturesque Landernau, visiting the ancient church of St Thomas (named after the English Bishop of Canterbury, Thomas à Becket who was famously assassinated in his cathedral and venerated by catholics as a martyr) where Philippe pointed out the stone statues sculpted from local granite called kersanton, one most unusually of the virgin Mary reclining after child birth, we drove a few kilometres into the beautiful countryside of Brittany.

At the kind invitation of Philippe and his charming wife Sabine, we were to stay the next two nights at the Kermadec manoir. If our room in Paris was tiny, the one given us here was vast – with a fireplace too. The great stone building dating from at least the 13th century is difficult to keep warm so the Kermadecs winter in a snug town house in Landerneau, returning here for summer. Philippe showed us around the grounds; his small flock of Ouessant black sheep and woods of oak, holly and wildflowers. In a corner of a paddock carefully fenced off and heavily mulched he pointed out a Tasmanian Huon pine (Lagarostrobos franklinii ), also named for his illustrious kinsman, gifted by an Australian botanic society. Though it is called a ‘pine’ it actually forms a unique genus, some specimens in the Tasmanian rainforest are estimated to be 2,500 years old. This one seemed to be thriving in its new home, In one of the stone outbuildings, (being from Waiheke), I admired Philippe’s impressive stock of firewood that he’d chainsawed and split with his axe from old oak trees that had been uprooted in a fierce Atlantic storm. Back inside, joined by Jean-Pierre, Philippe lit the fire while Sabine poured everyone pre-dinner whiskies. We chatted away watched over by portraits of Kermadec ancestors in naval uniform. I have to say it was linguistically challenging for me (and embarrassing) to explain in response to our host’s questions about what had happened to the Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary, the visionary massive marine reserve of some 620,000 square kilometres, announced by prime minister John Key to the United Nations General Assembly in 2016 – and why eight years on, successive NZ governments, made up of all the political parties represented in our parliament, have failed to honour this commitment. Waiheke readers will understand more than most Philippe’s disappointment and how hard it is to get the current New Zealand political class and officials to ‘walk the talk’ when it comes to marine protection; a field in which New Zealand was once a proud world leader.The

Sunday morning, with Jean-Pierre driving, we headed for the Crozon peninsula, on the southern side of the Rade de Brest, of Finisterre, the great and quite beautiful Atlantic harbour, to find the former estate of the Du Clesmeur family. Ambroise Bernard Le Jar du Clesmeur another Breton noble, at the astonishing age of 21 succeeded Marion Dufresne as expedition commander after Marion and 24 of his crew were killed at the Bay of Islands in 1772. By the time of the French Revolution in 1789, Du Clesmeur was a senior officer in the Marine royale, and a decorated veteran of the American war of Independence. But soon after, with the advent of the revolutionary ‘Reign of Terror’ he and his family had to flee the country along with hundreds of other nobles. At first Philippe and Jean-Pierre traced Du Clesmeur to the émigré community of the St Pancras district in London, but after that, despite their best efforts the trail goes cold. Another of product of their research covered in my book – also with an element of mystery, is the story of Louise Girardin. This young woman, a widow at the time being deserted by a feckless lover and having a baby out of wedlock, in 1789 travelled from Versailles to Brest, which was and still is a major French naval base. Disguised as a man, she was carrying a letter addressed to Madame Le Fournier d’Yauville, the Kermadec brothers’ widowed sister. Madame d’Yauville’s, late husband had been a naval officer from a family which had been attached to the royal household in Versailles. While the author and contents of the letter will never been known, because of it, at least three senior naval commanders, Kermadec, Du Clesmeur and Bruny d’Entrecasteaux, contrived to break navy regulations, signing on Louise disguised as a man, ‘Louis’, as Admiral d’Entrecasteaux’s steward for his Pacific expedition to search for the lost ships of La Pérouse. Maintaining her disguise Louise in 1793, was the first pakeha woman to see New Zealand and Māori off Spirits Bay. Sadly, along with many of her crew mates she died from a tropical disease contracted in the Dutch East Indies, on the voyage home. By that time both the voyage commanders had also died. Jean-Michel Huon de Kermadec, stricken with tuberculosis, passed away only a few weeks after sighting North Cape and the islands which were to immortalise his name, mourned by his shipmates was buried on a little island at Balade, New Caledonia.

We found the former Du Clesmeur manoir deserted but clearly someone had done a fair bit of restoration, especially on the tiled roof. Through a window we saw childrens’ books and toys. A holiday home for a wealthy city executive? But given the rank grass and weeds, it had been deserted for at least two years. ‘Divorce’, I suggested to Philippe. He agreed.

That evening, joined by Sabine at Jean-Pierre’s spic and span, ship-shape cottage, decorated with nautical paintings, and other sea-faring memorabilia, Jean-Pierre after driving all day still managed to whip up a delicious crayfish dinner.Given the long summer twilight it was surprisingly late by the time we got back. Next day it was time to return to Paris to begin my research in earnest. Philippe drove us to Landerneau station, refusing to leave until the train, which was late, arrived. I noticed the solicitous way he chatted with the local people and concluded this was part medical doctor and part Kermadec noblesse oblige.