Auckland’s Light Rail saga

How a sensible project with no funding was flipped to become the opposite

The Minister of Transport, rather like a desperate gambler having a bad night at the casino is reportedly ‘doubling down’ on the government’s ill-starred light rail project. He now wants to extend light rail to the North Shore. The problem is five years on the government has yet to build anything to extend it from, not a millimetre of track. And embarrassingly, has been unable to produce a business case. Nevertheless, Treasury last year costed the present scheme (City to Airport) at $14.6 billion up to $29.2 billion. Fortunately for the minister (but unfortunately for the New Zealand taxpayer) it’s not his money at stake here. And if one thing is certain about this project, it’s we, the taxpayers, who are most likely to lose our shirts.

The Auckland light rail project has, in all its various iterations, been plagued with problems going back as far as 2016. These are not going away anytime soon because they are the inevitable result of a politically-driven shift from the purpose of the original light rail plan set out in the Auckland Regional Land Transport Plan of 2015-25. This was if anyone can remember a technological step-change from buses to light rail vehicles (trams) on city arterials, specifically Sandringham, Dominion, Mt Eden and Manukau Roads, Symonds and Queen Streets, to overcome future grid-lock congestion revealed by transport modelling at that time. It was a future network approach centred on the CBD, rather like Melbourne’s but of course on a much more modest scale. This sensible but unfunded plan was suddenly and mysteriously replaced in mid-2016 by a proposed 24 km single line to Auckland Airport (the latter subsequently rebranded as ‘Māngere’). In 2017 this became a keynote government policy, and was promoted as a catalyst for investment in intensified development along this corridor, originally Dominion Road, and now apparently Sandringham Road, (much of which is now planned to be in a tunnel).

The construction of this one thin line, according to its promoters led by then Transport Minister Phil Twyford, was to be a ‘game changer’ and a ‘magnet’ for property investment. That a scheme with 8 tram stations rather than 20 bus stops on an intensified Dominion Road was likely to exacerbate traffic congestion rather than reduce it was evidently never considered. ‘Game changer’ or not, the scheme was not designed for the convenience of public transport users – whether they be future airport passengers (too slow) or local residents (not enough stops). That minister has long since gone, but the legacy of strategic confusion still reigns.

Despite five years of head-scratching by bureaucrats and consultants (the latter costing $60m at last count with a lot more to come), there is a fundamental contradiction lying at the heart of this plan. The light rail scheme is trying to deal with two separate public transport problems at the same time, serving Auckland Airport, whose passenger throughput is predicted to grow in the post-pandemic world to reach estimates of 40 million in ten years, and reducing congestion by providing better public transport (in one corridor) on an intensified isthmus.

Attempts to achieve these two objectives with a single solution are suboptimal for both. They are, in effect, contradictory. The faster and more convenient the airport service (the fewer stops, currently 18, the better), the more inferior the PT service along the corridor – and vice versa. It is this strategic confusion that no amount of determined attempts to hammer a square peg into a round hole can solve. This stubborn contradiction will be a key part of the explanation for the failure to produce a business case, especially the benefit/cost analysis usually mandatory for taxpayer-funded transport projects.

Undeterred, the government has set up a company ‘Auckland Light Rail Ltd’ with a board of appointed directors chaired by an ex-Wellington politician Dame Fran Wilde, and a CEO, Tommy Parker, ex-NZTA and ex-Arup NZ, a tunnelling company.

Auckland Light Rail Ltd, despite failing to come up with a business case or much of a coherent plan, has now embarked on an expensive public relations campaign. Despite making little tangible progress in actually building light rail, its greater ambitions are becoming clear. Apart from the single line to the airport, Auckland Light Rail Ltd wants to build light rail to the North Shore, to the Northwest, and even to run light rail in competition with trains down the future Avondale to Southdown rail corridor.

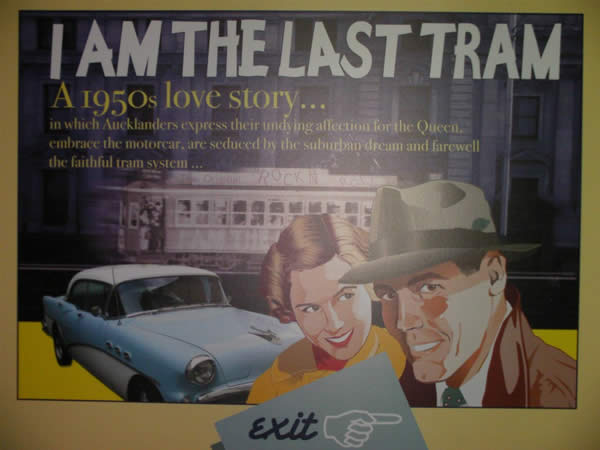

Sizzle but no sausage. Auckland Light Rail Ltd’s pr campaign on display at Auckland Airport. Noone ever asked airport passengers what mode they would prefer

The ambition, no less, is to build a parallel passenger rail system in Auckland, with separate rolling stock, different gauge lines, caternary, signalling, etc., to, in effect, duplicate the heavy rail system for which the ratepayers and taxpayers of Auckland have already invested so dearly. Leaving aside the multi-billion-dollar costs of the CRL, Auckland ratepayers are still paying down a c500 million dollar loan for electric trains, with more to come. Such duplication is not rational and certainly not affordable for a city and country of this scale.

Meanwhile, the elephant in the room, the other, (previous) government-created entity, CRL Ltd, has announced another billion-dollar blowout, taking the cost from the original $2.4b in 2011 to $5.49b. The completion date, mirage-like, has again drifted further into the distance, this time to ‘late 2025’. Further costs and more delays are to be expected.

However, despite the lamentable failures of its Link-Alliance construction, the City Rail Link project is at least coherent in intent; a 3.4 km double-tracked heavy rail tunnel linking the existing rail corridor under downtown Auckland to the Western Line at Mt Eden. Similar projects have been on the books since the before mid-20th century. Given this scale of investment, would it not make sense to at least scope the use of heavy rail for future long-distance services, e.g. to the Airport and the North Shore, rather than light rail trams, the optimum use for which is as a short distance people mover?

The over-reliance on consultants, the hallmark of the Auckland light rail project, is undoubtedly due to a deficit of technical knowledge. This has always struck me as peculiar given that ample know-how and experience exist only three hours flight away in Australia. A key indicator of this knowledge deficit is the constant, vacuous assertions of officialdom that light rail is ‘rapid transit’. However, as the builder and manager of the successful, 20 km with 19 stations, G-Link light rail on Australia’s Gold Coast, Phil Mumford told an Auckland Transport delegation I was a part of in 2015 – “Important thing to remember guys light rail is NOT rapid transit – its mass transit”.

Unlike our bureaucrats and consultants, Mr Mumford knew what he was talking about. The popular G-Link, competently built and operated since 2014, moves thousands of people per day (‘mass transit’) in comfort and with zero emissions, but its average speed (30km per hour) is still slower over comparable distances than buses and trains. That said, it is considerably faster than Sydney’s newest light rail service. While light rail has many city-building benefits, ‘rapid transit’ is not one of them. To proceed on the basis of this misunderstanding is a fundamental error.

End Part One

____________

Part Two

The history of Auckland’s light rail project has been one of strategic incoherence and poor technical understanding and advice. The projected costings have gone from $3.5 billion through various variations to $6 billion to the present plan for light rail in a tunnel costing $14.6 billion, to probably $29.2 billion. This would be a record per kilometre cost of any light rail build, by a considerable margin, anywhere in the world.

The only beneficiaries thus far have been the private consultants battening on as the project refuses to die and blunders onward, haemorrhaging public money and stinking of political death.

There is, I believe, a way forward out of this mess, one which will help the government in the short term and Auckland and the country in the long.

I suggest it’s time for another look at Auckland Transport’s original light rail plan, set out in the draft Auckland Regional Land Transport Plan of 2015-2025 and which received clear support from Aucklanders’ public submissions – the last time they were asked. This was for a conventional Melbourne-style light rail network on Auckland’s busiest arterials as an analogue for buses. A good plan but with no funding. Interestingly, now we have the opposite – a thoroughly bad plan fueled by the confident expectation of billions of dollars of funding. A considerable amount of technical work and planning was completed by Auckland Transport before this original project was mysteriously shelved late in 2015 early 2016. Also, at that time, set out in the first version of the Auckland Plan (2012) was the long-standing commitment to extend a heavy rail connection to Auckland International Airport upon completion of the City Rail Link project.

Late that same year, in November 2015, I was present at the Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron when mayoral candidate Phil Goff MP launched his mayoral campaign, pledging to build a light rail line to the airport! Things, if you forgive the expression, went off the tracks from that moment onwards – and have remained that way ever since. Goff, after handing his ‘pledge’ on to his Labour Party parliamentary protégés Twyford and Wood, quietly distanced himself from the idea.

How did this all happen? Some explanation is needed here. I don’t profess to know the full story but I can say, despite the generally positive response from Aucklanders I have good reason to believe AT’s light rail plan unveiled in early 2015 was received with some consternation – if not anger – at the highest levels in Wellington, still grappling with Auckland’s City Rail Link project. Not the least in the office of the then Minister of Transport Simon Bridges. I was in Wellington early in February doing some library research when I received a phone call from the Opposition spokesperson on Auckland issues Phil Goff who seemed a little disconcerted himself about the RLTP light rail initiative. I reassured him it all made sense in terms of future planning and I promised to get him a briefing with a senior manager in AT. (A situation not without some irony as it turned out). Little did I know at the time that under intense government pressure AT was beginning to back off the light rail network plan and cribbing together a compromise. So, the briefing with AT I arranged for Goff according to what he later told me, did not turn out the way I had presumed. In June 2016 the AT Board following the board of NZTA, formally resolved to abandon the long planned heavy rail connection to Auckland Airport in favour of ‘high capacity’ buses – and light rail:

“1. That Management discount heavy rail to the airport from any further option development due to its poor value for money proposition;

2. Instructs Management to:

a) Develop a bus based high capacity mode to the same level of detail as the LRT option to allow a value for money comparison with the LRT option and submit this to ATAP for consideration;

b) Refine the LRT option further to address the high risk issues as articulated in this paper;

c) Report back to the Board on the findings of the bus based high capacity mode and LRT comparison.

d) Progress with route protection for bus / light rail, not heavy rail;

etc, etc.,

One director (Mike Lee) recorded his vote against”

Under the government of the day’s non statutory ‘Auckland Transport Alignment Plan’ (ATAP), light rail to the airport was relegated to sometime around 2030 – buses were to be the preferred solution. That was to change in 2017 with a new government and the advent of Minister Phil Twyford. Only the Official Information Act is likely to reveal the full story but this is how I believe we got to the situation we are in today.

Given these problems (which very much include ‘value for money’ or the lack of it) there is merit in at least exploring an alternative approach that would deliver a more financially responsible solution without retreating from the original concept of a future light rail system in Auckland. The strategic objective of this would be to reduce road congestion, move more people around the city, significantly uplift Auckland’s woeful public transport patronage (currently still just over 60% of pre covid levels) while reducing carbon emissions. This by way a fresh look at the original plans, the staged replacement by light rail of bus services on Auckland’s congested main arteries. Judging by overseas experience, especially in France and Australia, this would enhance urban quality of life, but it would also have absolutely nothing to do with expensive tunnels, nor should it have anything to do with Auckland International Airport. It may or may not be ‘a magnet’ for property investment, which could be a happy outcome, but it cannot be a strategic purpose.

An alternative proposal backed by NZ Transport 2050 would involve building the light rail system in sequenced stages (e.g. 5 km packets). A sensible approach in the current economic climate. Starting from the city waterfront, the first stage would link high passenger nodes close to the Auckland city centre, which are not currently well served. This would entail a line via Symonds Street (as in the original RLTP) serving Auckland University and Auckland hospital. The line could terminate at the hospital or link to the existing Grafton Rail Station. The subsequent stages to be rolled-out after further planning and public consultation.

A key part of the package would be to capitalise on the massive spend on the City Rail Link by restoring the original Auckland Plan (2012) objective of linking the Main Trunk Line (heavy rail) with Auckland International Airport at Puhinui, just 7 kms away. This would also place the Waikato and the city of Hamilton within convenient reach of Auckland International Airport.

However I would add a final caveat, and that is no major rail or similar transport construction project (e.g. the proposed harbour crossing), should proceed in Auckland until there has been a thorough and independent review of the City Rail Link project, what went wrong, and the lessons from this taken on board. The objective should be to build rail infrastructure to build the country, not bankrupt it.

This article was published in two parts in Newsroom in April 2023.