‘Sea Change’ versus democracy in the Hauraki Gulf

It’s fair to say that the democratic element of our society has been weakened in recent years, a by-product of the neoliberal revolution that has swept across the western world. Unfortunately this revolution didn’t stop with the disappearance of Sir Roger Douglas down the political plughole of the Act Party; we now know only too well that this ‘rust never sleeps’ revolution is ongoing. Events around the world and right here at home under the Super City confirm this disquieting trend.

I guess in a small island community like Waiheke we are more sensitive than most to the declining role of democracy in our daily lives. That is why a substantial number of Waiheke residents would cheerfully break away from the Super City tomorrow and restore genuine local government – if the authorities would allow it. But of course they will not. The truth is democracy, accountability and the rights of ordinary citizens count for a lot less than what they used to.

That being said I have to admit I was still rather taken aback to read of the vehemence of the criticism of elected politicians of the Hauraki Gulf Forum by Environmental Defence Society policy director Raewyn Peart in her recent Gulf News article about the Hauraki Gulf and so-called ‘Sea Change’.

I have known Raewyn Peart since I was chairman of the Auckland Regional Council (ARC). She has worked on and off as a consultant for the Hauraki Gulf Forum for 10 years or so and also for ‘Sea Change’. One wonders whether it was just naivete or being in the constant company of fellow-minded consultants that emboldened her to reveal such open contempt for elected ‘politicians’ – and by implication the democratic process.

As an elected politician and a Hauraki Gulf Forum member I will defend myself by telling the people of Waiheke the plain truth as I see it about the troubling elements of this so-called ‘Sea Change’, and about the high stakes power play currently underway over the ownership and control of the Hauraki Gulf.

My own role as a Hauraki Gulf environmentalist goes back a long way before I became a politician in 1992 when I was elected to the ARC, and certainly long before the establishment of the Hauraki Gulf Forum. As for Waiheke’s other elected politicians involved in the Forum, I rate John Meeuwsen and his alternate Paul Walden as public representatives of the highest integrity.

Raewyn Peart’s article was apparently to promote the merits of ‘Sea Change’ but so intent was she on attacking the Hauraki Gulf Forum – or should I say its elected members – that she didn’t get round to spelling those merits out. The Hauraki Gulf Forum is not and was never meant to be a governing body, as she seems to think. Its role and responsibilities are set out very clearly in part 2 of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act. In short it is meant to be an interagency sounding board; a clearing-house for sharing information between the government departments, councils and the six Māori representatives of manawhenua, with responsibilities in and around the Hauraki Gulf and to advocate for the Gulf. The Hauraki Gulf Forum has its limitations but that it is actually more well-known than the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park itself (Part 3) is a pretty sad commentary about the lack of willingness of successive governments to create a genuine, not just a paper, national marine park in the Hauraki Gulf.

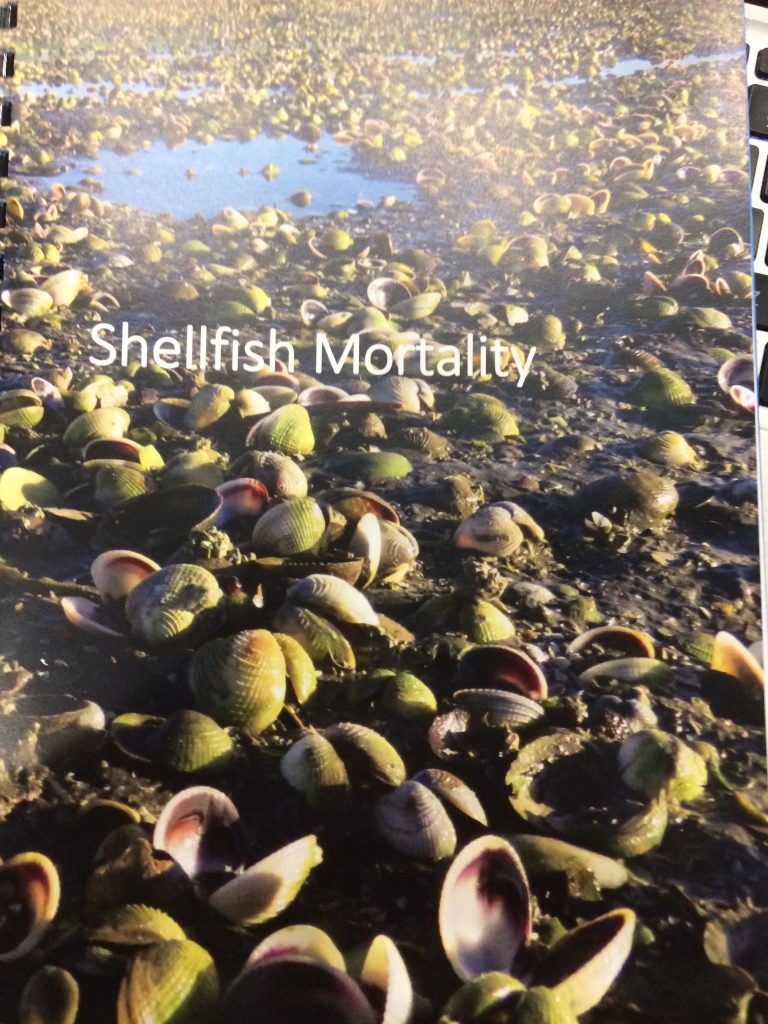

Massive shellfish mortality in a marine reserve. This, the result of heavy silt run off from large-scale earthworks in a previously rural area adjacent to the Okura-Long Bay Marine Reserve. To their shame neither Auckland Council nor the department of Conservation took any action against the influential property developer.

It is also important to note that ‘Sea Change’ is meant to be a marine spatial plan for the Hauraki Gulf. From the outset its advocates including Raewyn Peart seemed to believe that a ‘spatial plan’ in itself would somehow achieve environmental enhancement of the Gulf. Those of us on Waiheke, familiar with bureaucratic plans are only too aware that they can also achieve the very the opposite of the stated intention.

Readers will find it ironic, given the bile now targeted at the Hauraki Gulf Forum, that when it came to leading and overseeing this spatial plan process, the Hauraki Gulf Forum was deliberately by-passed –for a role which any reading of the Act would have concluded it was tailor-made for. Instead an ad-hoc ‘Project Steering Group’ based on racial lines, 8 manawhenua and 8 others representing government departments and councils was set up. ‘The Project Steering Group (the mana whenua–agency governance group)’ to give its full name was co-chaired by lawyer and businessman, chair of the Maunga Authority, chair of the Hauraki Collective and Ngati Maru Treaty negotiator Paul Majurey, and Cr Penny Webster of Rodney, the former ACT MP who revealed her attitude to the Hauraki Gulf by voting against the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act in 2000. Curiously this ‘Project Steering Group’ and its membership is not mentioned at all in the ‘Sea Change’ report and references to it on the internet have been taken down. The ‘Sea Change’ report only refers to “key leaders with an interest in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park who in October 2013 were invited to participate in democratic process to from the Stakeholder Working Group.” To head the ‘Stakeholder Working Group (SWG)’ was an ‘independent chair’, merchant banker and CEO, now chairman of Deloittes, Nick Main was appointed and then after him from 2015 a lawyer from Wellington, director (now chairman) of the law firm Buddle Findlay, Paul Beverly a specialist in Māori law and Treaty settlements.

After adopting the snappy corporate brand ‘Sea Change’, (to give it its full name ‘Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari’) those involved made it clear they were not particularly interested in working within (or really even that much aware of) the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act.

It was all very much a behind-closed-doors process, with the SWG dominated by, as Raewyn Peart puts it, a ‘collaborative group’ representing aquaculture, commercial and recreational fishers, dairying and forestry sectors and Treaty claimants. There also two ‘environmentalists’ one of whom was Ms Peart. Meanwhile the general public, including those island communities who live in the Gulf, were effectively shut out.

The Waiheke Local Board, which during this time initiated scientific research into marine ecosystems around Waiheke Island and commissioned professional public opinion surveys on marine reserves incredibly had the door closed on it by the ‘Sea Change’ bosses and its evidence rejected. The SWG finally reported its findings in December 2016, a year behind schedule. Interestingly on the critical issue of marine protection ‘Sea Change’ turned out to be weak indeed. In fact the most detailed measure advocated by ‘Sea Change’, but one that is not broadcast too widely, is a 2550 square kilometer ‘Ahu Moana’ which would cover the total length of the Hauraki Gulf coastline from the beaches extending seawards for one kilometre, which would also encircle every Gulf island including Waiheke. These would be, according to ‘Sea Change’ co-governed ‘50-50’ by ‘Coastal hapū/iwi and local communities’. What this would achieve in regard to environmental protection remains unclear.

On the pressing issue of marine pollution, ‘Sea Change’ soft-pedals the pollution of the Firth of Thames by intensive dairying and of the scale of the pollution of the Waitematā Harbour from human sewage. The fact that at least 2.2 million cubic metres of sewage-contaminated stormwater pours into the Waitematā each year is not mentioned nor that that the proposed Central Interceptor is designed for sewage not stormwater and as Watercare has pointed out does not provide a sustainable solution to contaminated stormwater pollution.

In mid-2017, three years after shutting the Hauraki Gulf Forum out of its statutory role, ‘Sea Change’ independent chair, Mr Beverly appeared before the Forum urging that it agree to reform itself on racial ‘co-governance’ lines. It was at this point that Waiheke’s Paul Walden intervened to move a procedural motion, reminding the Forum that before supporting any recommendations to change the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act (properly the role of Parliament), Forum members must consult with their parent agencies and the general public. To the chagrin of ‘Sea Change’ proponents the motion was carried.

Could the proponents of ‘Sea Change’ really have been that ignorant of legal processes? Or was this a ‘try-on’ to pre-empt and pressure the government on matters properly dealt with by Parliament and the Treaty settlement process?

I’m not bothered about being criticized for supporting local democracy and for calling out ‘green washing’ and corporate dominance of public life when I see it, but I am really worried by the attempt to undermine the concept of no-take marine reserves and to repeal the Marine Reserves Act 1971. Right now there is a concerted campaign to put pressure on the new Minister of Conservation Eugenie Sage to do just this. This would be a retrograde step for nature conservation but also a dangerous precedent not only for the integrity of hard-won existing marine reserves but for our terrestrial reserves and parklands. The network of pathetically small ‘Type Two Marine Protected Areas’ which ‘Sea Change’ proposes whatever they are, are not ‘no take’. Even so-called ‘Type One’, ostensibly ‘no-take’ marine reserves, would be placed effectively under the control of ‘hapū/iwi’ who would also have the right to resume ‘customary take’ in them. These would also be subject to a 25-year ‘generational review’ (whatever that means). Which brings me to the another aspect of ‘Sea Change’ which Raewyn Peart places much emphasis on, that is under the ‘Sea Change’ regime, democratic representation on the Hauraki Gulf Forum would be replaced by ‘co governance’ by what she calls ‘strong leaders’ (presumably unelected) and the Forum itself would be reconstituted as a ‘controlling agency’ which would in its decision-making “take into account future Treaty settlements.”

Leaving aside the human politics and getting back to the fundamental issue of the marine environment, I believe the most critically important measure to protect and enhance the Hauraki Gulf is a simple one, marine reserves.

Marine ecosystems in the Hauraki Gulf are under enormous pressure from overfishing and pollution. We need to change our attitudes; it is time to start putting nature first. The very positive conservation work happening on the land, especially on Hauraki Gulf conservation islands demonstrates just what really can be done. It was Waiheke volunteers, whom we should remember, began the game-changing restoration of Tiritiri Matangi back in the mid-1980s. We just need to apply that successful restorationist philosophy to the sea by creating a network of no-take marine reserves. Not only would this be the practical recognition of the intrinsic value of ecosystems but setting some areas aside from exploitation will mean there will be more fish for future generations. The Hauraki Gulf belongs to all of us and should not be handed over to a non-democratic elite and their consultant advocates.

This article appeared in Gulf News 21 June 2018.