Strangers in the 21st Century

Auckland and New Zealand Politics without Bruce Jesson – a lecture on behalf of the Bruce Jesson Foundation, by Michael Lee chairman Auckland Regional Council at the Maidment Theatre, Auckland University, October, 2008.

Bruce Jesson about to move the notice of motion (co-sponsored with the author seated to his right) to halt the ARC sale of the Ports of Auckland, 16 March 1992

Taking up Bruce Jesson’s books again when I began to prepare for this lecture – and reading again that clean, simple, but incisive writing style, the wry self deprecating humour and the clever use of the dialectic – reminded me how much the New Zealand political scene, had been diminished by Bruce Jesson’s passing in 1999. Interestingly it brought back to me the feeling I had when Bruce died – how to articulate this? Many of you I guess must have experienced similar feelings yourselves. But for me especially in terms of politics, that extra interest, that intellectual challenge, the extra spark that Bruce Jesson brought to New Zealand politics had gone for good. And we are all the poorer for it.

The title of this lecture ‘Strangers in the 21st century’ has different layers of meaning – on a personal level, for me it is about operating in politics in the absence of the advice and intellectual companionship of Bruce Jesson. In a wider sense it relates to our society’s alienation from the past and its uncertainty – uncertainty perhaps is not the right word – lack of contemplation – about the future. It was argued by Bruce on more than one occasion (for instance in the chapter The State of Amnesia in his last book Only their Purpose is Mad – that we New Zealanders are careless – perhaps deliberately forgetful – about our history – and there is a price we pay for that. As the Roman politician Cicero once said – “to live in ignorance of the transactions of the past is to always live as a child.”

At the outset I should point out that I count myself lucky in not only having known Bruce Jesson as a friend, but I also was fortunate to have served alongside of him during what I believe to be some of the more dramatic and important events in the recent political history of the Auckland region – when the continued public ownership of the Ports of Auckland and other regional assets hung in the balance. During those rather tumultuous months of 1992 after being elected to the Auckland Regional Council soon after Bruce and due to an ARC convention about seating members in alphabetical order, we sat next to each other in the debating chamber. That was an unforgettable experience for me.

So I want to talk a bit about history – specifically (and not surprisingly I guess) the history of local government in Auckland. History does repeat itself as Hegel and Marx famously noted. I think that in examining Auckland’s history we can discern recurring tendencies and patterns. This I believe can be instructive for how we can better manage and develop Auckland now and in the future. This will lead me to the present day debate on the restructuring of Auckland local/regional government, specifically in terms of the Royal Commission on Auckland Governance. Finally I would like to pose the question – that if major changes to the governance, the constitutional arrangements of Auckland, are deemed essential – then what about the country as a whole.

Now to begin the story, the first steps towards the establishment of local government for pakeha settlers came in 1845 when the Colonial Office in London decided that New Zealand should have formal local government (part of getting the colony to pay for it own upkeep) and duly communicated this to Auckland – to the new Governor George Grey. By all accounts this was not well received at Government House.

“During 1845 Earl Stanley (Secretary of State for the Colonies) had ordered the establishment of elective municipal councils in Auckland, New Plymouth, Wellington and Nelson, with powers to pass by-laws and levy rates. Grey, having so easily disposed of Adelaide’s once troublesome council now wrote to Stanley to express his fears that the greedy speculators and merchants who swarmed in Auckland would be those most likely to be elected to local bodies by the ignorant settler masses.”

A draft constitution for New Zealand drawn up in London proved to be unrealistic for local conditions and Grey managed to avoid implementing it while he drew up his own more practical constitution, which came into force in 1853. George Grey’s constitution provided for elected provincial councils in Auckland, Wellington, Canterbury, Otago, Taranaki and Nelson.

As Grey predicted the settler capitalists quickly ascended to political power in the colony but despite Grey’s contempt for them – especially the Auckland settler capitalists – it wasn’t too long before Grey found himself in an unholy Alliance with the Auckland business set when it instigated the invasion of the Maori King’s lands in the Waikato. Of course for them the New Zealand War was purely about seizing land for speculative purposes, for Grey the motive for war was all about Empire and Imperial sovereignty.

After an inauspicious start, local government in Auckland for a time became the responsibility of the Provincial Council, which worked reasonably well. Unfortunately from the outset the provincial councils and the central government could not get on – and bickered constantly. The situation became so bad that the Auckland provincial council even thought about seceding from the rest of the colony. This unhappy state of affairs lasted until the provinces were abolished by the central government in 1876

After the capital was transferred to Wellington in 1865 there was renewed pressure for local government and yet another Auckland City Council was established in 1871 and this same body has remained in existence to this day.

Not surprisingly, the free-wheeling individualistic culture of Auckland – very much based on speculation and subdivision of land, resulted in a city which over time sprawled out in a somewhat haphazard fashion and which continually tended to outgrow its infrastructural carrying capacity. I am deliberately simplifying things here because Auckland’s early leaders did lay out the town in a coherent plan and did create a number of beautiful buildings, in my opinion, far superior to anything done in more recent times – I am talking about the Town Hall, the Customs Building, the city library (which is the art gallery) the Ferry Building, the Central Post Office, and of course the superb Auckland War Memorial Museum.

However for its first 100 years or so, Auckland’s main infrastructural problems related to the supply of bulk water and especially the disposal of sewage – both of which proved to be inadequate to cater for the constantly growing population. Over those years the city experienced periodic crises because of this. The chronic sewage disposal problem was underlined in 1888 by a serious outbreak of typhoid in Auckland.

Up until the mid 20th century then, it was sewage and not transport, which caused the major headaches and was the focus of considerable public and political debate in Auckland.

For the first half of the 20th century raw sewage was conveyed by the Hobson Bay sewer line and dumped into the sea at Orakei (the holding tanks are where Kelly Tarlton’s aquarium is today). As the city grew in size the pollution of the harbour and neighbouring bays from this sewage became greater and increasingly offensive.

Eventually in 1931 the authorities decided on a major new scheme in which Auckland’s sewage would be conveyed by an undersea pipe to Browns Island where after minimal treatment it would discharged out of sight and out of mind into the Rangitoto channel. The Browns Island affair as it came to be known turned out to be an extremely bitter, acrimonious business, which ran on for nearly 25 years. This cause celèbre led to the launching of a previously unknown businessman Dove-Meyer Robinson into local body politics. Robinson became a leader of what was probably the city’s first urban environmental group, the Auckland and Suburban Drainage League.

Robbie, as he came to be known, eventually concluded that the best way to fight the system was to take it over – which he proceeded to do. He was elected to Auckland City Council in a by-election in 1952, and in 1953 he was followed by four of his ‘United Independent’ supporters including Professor Kenneth Cumberland future head of Geography department at Auckland University. Together they proceeded to take control of the Drainage Board and halted the Brown Island project – though contracts had been signed and construction was already underway – (imagine that?).

To settle the vexed question of the city’s sewage disposal, they called in a panel of international experts, which recommended the revolutionary technology of oxidation ponds and for these to be located at Mangere. This happily was exactly the solution Robbie had always wanted. Robbie was elected Mayor in 1959 by grateful Aucklanders and re-elected to that office for a record six times.

Dover-Myer Robinson, Auckland’s most popular civic leader. Six-times mayor of Auckland and founding chairman of the Auckland Regional Authority

Apart from the legacy of a (relatively) clean Waitemata Harbour, Robbie’s capstone achievement was the establishment of the Auckland Regional Authority in 1963.

All throughout the 20th century parochialism, infighting and a chronic lack of unity had been an unhappy feature of Auckland local government. By 1960 there were 32 territorial authorities (city, boroughs and counties) and some 15 ad hoc bodies. In the post World War II era when Auckland’s population began to grow rapidly, there was a realisation by some of the more farseeing city leaders that if Auckland was to cater for that growth some sort of strong and co-ordinated regional planning and development authority was required. In 1963 after three attempts, the Auckland Regional Authority Act was passed through parliament – after years of intensive lobbying by Robinson and others.

The ARA was the New Zealand’s first regional government since the abolition of the provinces. Its responsibilities included bulk water supply, sewage reticulation and treatment, public transport, waste management, management of Auckland International Airport, the Waitakere Ranges Centennial Memorial Park – and regional milk distribution.

The new Authority quickly embarked upon an era of major infrastructural development, which I will call the era of Post War Building.

In terms of bulk water supply, from 1965 to 1977 the ARA built five new major dams in the Hunua and the Waitakere ranges in 12 short years, doubling the number of dams and increasing Auckland’s bulkwater storage capacity by over 385 %. At the same time Robbie’s baby, the Manukau Sewage Purification Works, (now called Mangere Wastewater Treatment Plant) and the network of main interceptors and pump stations were comprehensively upgraded

The ARA also constructed four major landfills and two refuse transfer stations processing about 70 per cent of Auckland’s rubbish.

The ARA also started buying land – mainly coastal land as part of the regional parks network. From the 1950s regional planners like F.W.O. Jones realised the need to protect outstanding coastal landscapes from the subdivisions which began to appear after the war. Also as Auckland was some 400 km from the nearest national park, provision would need to be made for the recreational needs of the region’s growing working population.

In terms of public transport throughout the sixties, seventies and eighties, the ARA building from the assets of the old Auckland Transport Board progressively bought up and amalgamated numerous private bus companies. By 1989 the ARA was operating the country’s largest urban bus fleet.

Faced with the growing problem of traffic congestion the ARA also built regional roads, including the Greenlane to Balmoral arterial, the Avondale NewLynn by-pass, upper Queen Street to Dominion Road, the Pakuranga Highway and Bridge and the upper harbour crossing at Greenhithe.

However, one of the most interesting and visionary ARA projects was one that never came to fruition. Known as Robbie’s Rapid Rail this was an ambitious scheme to upgrade, extend and electrify Auckland’s suburban rail network. It was developed by the ARA and the New Zealand Railways Department, and energetically promoted by Dove-Meyer Robinson. In 1975 the project had gained the approval of the Kirk Labour government but tragically it was thrown out in 1976 by the incoming National government of Robert Muldoon.

The rejection of Robbie’s Rapid Rail, followed by the completion of the massive Mangatangi Dam in 1978 – signalled the beginning of the end of the era of Post War Building in Auckland.

By the 1980’s the ARA had began to fail.

Its difficult to explain why such a successful organisation should fail. The oil shocks of the 70s perhaps led to a loss of confidence. A rather hostile National government was followed by a Labour government in 1984 which was as we know preoccupied with a free market agenda and was essentially indifferent to the building of infrastructure. The new wisdom from Wellington was that the market having at last been unleashed would now take care of most things. Centralised planning had become ideological anathema. In the brave new world of Rogernomics, of ‘crash on through’ deregulators and ‘dashing corporate raiders taking on the world’, the ARA began to appear somewhat clunky and old-fashioned.

There also remained the old problem – the so called ‘Auckland disease’ – hostility from the city and borough councils, which resented the ARA’s growing domination and objected to its cost on their ratepayers.

In 1983 a ticket largely organised by anti-ARA Mayors and borough councillors, calling themselves, with a distinct lack of historical authenticity, the ‘New Deal’, succeeded in winning control of the ARA. The ‘New Deal’s’ political programme was to prevent the ARA from doing what it was originally designed to do – in fact stopping it from doing much at all.

For all of these reasons the ARA stopped doing major capital works – yet the city continued to grow faster than ever. When the big infrastructure projects ground to a halt, the ARA lost momentum, it lost self-belief and soon enough it lost public support. Once it stopped doing major public works the ARA became a large, bureaucratic slow-moving target.

Auckland entered what can only be described as a period of distinct mediocrity – this was the time of a generation, in both politics and business, which reaped but did not sow.

What is interesting about the so-called ‘New Deal’ era was that the long standing tensions between the regional authority and the territorial councils became internalised – brought within the walls of the ARA as it were – consequently throughout the late 80s and early 90s the ARA became known for its political fractiousness.

1989 was a critical year for local government in Auckland. This was the time of the second wave of reforms of the Labour Minister of Local Government Michael Bassett, which involved major local government amalgamation. The winners were the new bulked-up city councils (in those days they were called the ‘super cities’) – the losers were the innumerable boroughs and county councils. The ARA which been strengthened by Bassett in terms of its elected representation in a first wave of reforms in 1986 was now given 80% of the shares of the former Auckland Harbour Board, now reconstituted as a port company. But at the same time the Authority had its named changed to the Auckland Regional Council. I believe there is a lot in a name – the ARA to a degree had not only lost its raison d’être, it had also in some ways lost its identity.

In 1988 ARA members had employed one of the new generation of high-flying CEO’s, Colin Knox (soon to be empowered under legislation to be the sole employer of council staff). This was controversial because when the new CEO was given a generous private sector-style salary package (including an inducement payment) it appeared to the media and the ratepayers as extravagant. Things got worse when the members were persuaded to build themselves a brand new headquarters – New Regional House. Unhappily this entailed a large debt (arranged by Fay Richwhite) at a usurious interest rate. During a time of economic recession the flash new building was seen as the height of self-indulgence. The word ‘profligate’ started to appear in media reports about the ARC. The more bad publicity the ARC generated – the more the council turned to expensive public relations consultants to improve its image – but rather than improving the ARC image, the pr effort itself drew more bad publicity.

This all was decidedly unhelpful and just as the New Right revolution began to burn its way through to local government .

The full blast of the New Right hurricane arrived in 1990 with the National government in the form of the Local Government Minister Warren Cooper. On form this guy was always going to be a problem for regional government in Auckland. Here was a new Minister of Local Government who was not only a rural South Islander, a hardline conservative and a Neo Liberal but also and perhaps most menacingly of all – a former small town mayor. The new Minister made it known he had no time for regional councils and wanted rid of them – especially the ARC.

In 1989 legislation had been passed forcing local bodies to corporatise their services – this particularly impacted on the ARC, now faced with the threat of abolition the ARC restructured itself fundamentally, corporatising its service departments, appointing boards of outside businessmen to run them and progressively removing them from direct political accountability. This was part of a phenomenon the then head of Political Studies at Auckland University Professor Richard Mulgan dubbed ‘Rogerpolitics’. Some of the ARC members objected – but most were demoralised. Everyone knew by then what the next step would be – privatisation. Meanwhile the city councils were formulating their own plans to take over the ARC assets.

It was about this time that Bruce Jesson was first elected to the ARC after scoring an upset victory standing for the new left wing Panmure Alliance in a highly publicised by-election.

This was of course budget year 1991/92 – the fiscal year of ‘the Mother of all Budgets’ and as a direct result there was a widespread mood of public anger – and mounting opposition to public asset sales. The new Alliance was the political beneficiary of all that anger. As an illustration of the tone of the times, the Alliance led in the opinion polls over both National and Labour and in February 92, came within a whisker of winning Muldoon’s old blue ribbon seat of Tamaki.

This is how Bruce saw the ARC when he walked through the doors in late 1991. “It [the ARC] had become a house very much divided against itself…I found staff members and councillors conspiring (successfully) against the chief executive Colin Knox. Councillors would spit insults at each other across the members room where councillors sipped their g & t s after the meeting. The ARC’s disunity left it vulnerable to attack from the city councils of the region who saw it as a competitor for influence and rates; and from Wellington bureaucrats who thought that services such as ports, buses and tips should be privatised.

The bad press that the ARC received was related to the debt associated with Regional House and this, as much as anything else, was the source of acrimony among the councillors… At that stage, I would say that the ARC councillors lost their sense of purpose, and that the acrimony prevented them properly defending the public service goals of the ARC.”

Early in 1992, the ARC, under pressure from the Government, and the usual suspects (Fay Richwhite was the sales agent) was poised to sell its 80% shareholding of the Ports of Auckland.

By co-incidence in December 1991, a month after Bruce’s election I was selected by the Alliance for a by-election for the ARC seat of Auckland Central. When I walked through the doors of the ARC in February 92 the Council was in a pretty advanced stage of selling the port. Meanwhile a fiery public campaign against the port sale was being whipped up by talk-back radio host Pam Corkery – (which I believe I helped instigate through a talk back call I made the day before voting closed for the Auckland Central by-election). The radio campaign fuelled an enormous public petition against the sale, which eventually filled a whole room and ARC members were invited along by Radio Pacific to view it. Some ARC members who had been supporting the sale began to waver.

Meanwhile the sale process was proceeding to timetable. Bruce and I thought it important that we seize the initiative – so we put together a Notice of Motion, with some help from other ARC members like Paul Walbran, calling for the Council to abandon the sale and cutting off funds for the sales process.

As a new member (I had come straight off a ship) the 28 member ARC struck me as being rather like parliament in those days. Not only because ARC members at that time were elected from parliamentary seats including two Maori seats – a legacy of the first Bassett reforms – but debates were invariably long and often heated – punctuated with noisy interjections and obscure points of order. The late Keith Hay for example might lead off a typical oration beginning “Mr Chairman, members of the Authority – when I left the Labour Party in 1946 to follow John A Lee…” and so it would go on.

Our notice of motion to halt the port sale had gained a huge amount of public interest, thanks to people like Philip English at the NZ Herald, and was debated in an atmosphere of high drama – it was supported by the other new Alliance members and supporters but also by old-fashioned conservatives like Keith Hay and Alan Brewster and by mavericks like David Hawkins and June Hieatt. In the end, the sale of the Port was effectively aborted by the narrowest of margins. This was the first defeat for a major asset sale up until that time.

Though this unexpected revolt embarrassed the National government, it was even more grimly determined to push through legislation to break the ARC in half and to strip its assets. Under the Local Government Reform Bill (No.2) of that year, ARC assets including Ports of Auckland, the Yellow Bus Company, Northern Disposal, Watercare, downtown properties, and the ARC debt (mainly on Regional House) – and Regional House were to be ‘divested’ to a new body – the Auckland Regional Services Trust (ARST). The ARC was to be left with the rump functions of environmental management, RMA planning and regional parks. In that legislation the ARC was expressly forbidden to own public transport infrastructure.

The Regional Services Trust, which was totally unique in New Zealand local government – it was clearly custom-designed to be an agent of privatisation. In terms of its constitution it had only one saving grace – its trustees were to be democratically elected. But the catch to this was that the trustees had to be elected at large – and the electorate was the whole Auckland region – some 700,000 voters. This was clearly designed to ensure that only very rich individuals or very well resourced political machines like the Citizens and Ratepayers would stand much of a chance of winning seats on it.

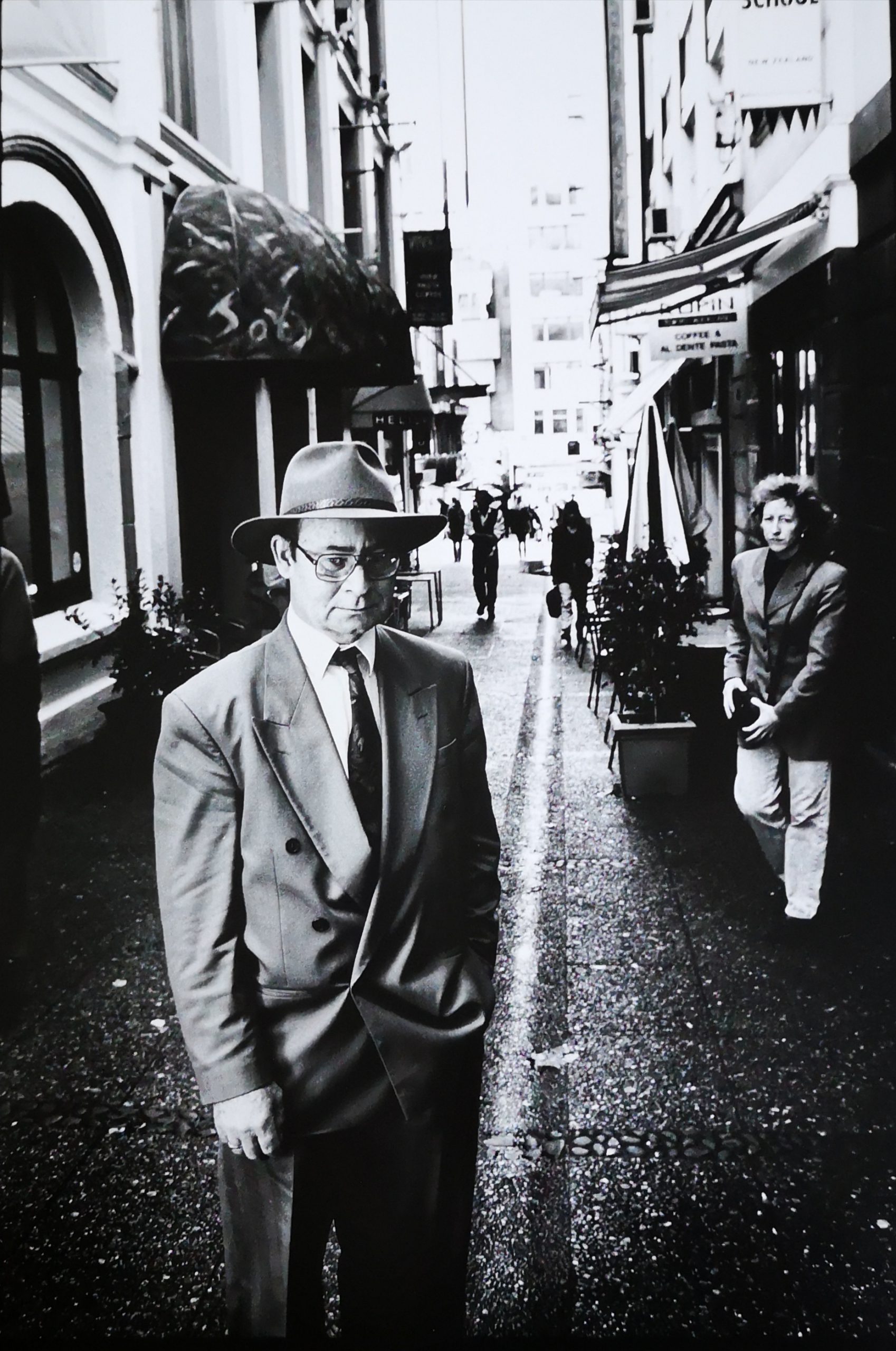

Bruce Jesson, writer, political thinker, New Zealand nationalist, chairman of the Auckland Regional Services Trust 1992-1995.

But the government officials who designed the Trust were to be confounded again. In the local body elections of October 1992 in a remarkable political campaign organised by Matt McCarten, the Alliance under the slogan ‘We won’t sell out, captured the ARST and Bruce became chairman.

The government and its officials though obviously surprised at the turn of events –reassured themselves, that because of the level of debt, Jesson and his colleagues would have to privatise the port and be forced into a humiliating back down. Again they were to be confounded. After years of advising politicians – ‘There is No Other Way’, the Wellington bureaucrats apparently had actually come to believe it. Bruce and his colleagues in a manner remarkably reminiscent of the way Robbie and his supporters captured the Auckland Metropolitan Drainage Board exactly 40 years before, took hold of the ARST and proceeded to transform its purpose to serve the public interest. They refused to sell assets.

Though they kept their promises or actually because their kept their promises what came to known in the media as ‘the Alliance dominated ARST’ did not get an easy ride. As Bruce explained in his Metro article ‘An Accidental Politician’ of November 1995.

The Alliance had made a lot of enemies in its brief existence, both nationally and in local government. We must have seemed insufferable with our belligerence and holier-than-thou politics. Now, we were the focus of attack and I was the obvious target.

For those three years Bruce was forced to live his life on a political battlefield. The attacks came in from all sides. Not only from the right wing media, but also from the Labour Party which saw the Alliance as a deadly rival, and behind the scenes to a degree even from the Alliance itself! As Bruce put it so memorably in the same Metro article:

“The situation of the trust was difficult enough as it was. The trust as a totally new body, was moving onto other people’s territory and we found ourselves at the centre of an incessant squabble. We squabbled with the ARC over the divestment of the assets and debt from them to us. We squabbled with the Auckland City Council over our jointly owned downtown properties. We squabbled with nearly all the councils about the control of the water and wastewater system. I had always thought of myself as a meek and mild little man, but I now discovered a cantankerous and stubborn side of my nature. After squabbling all day with other politicians, I would go to an Alliance meeting of an evening and squabble with them as well.”

To keep the ARST afloat in its first few months without selling assets ARST Chief Executive Mark Ford with a small group of financial advisers formulated a subordinate debt arrangement with the ARC – the debt to be repaid over 15 years. When Bruce retired from politics in 1995, the debt had been virtually paid off, the ARST assets were worth $1.8 billion dollars and as he pointed out in 1999 “few private sector companies performed as well during the six years the Trust existed”.

To the consternation of the political establishment a viable alternative to privatisation had been created – holding on to public assets – and managing them to create public wealth in the public interest. “Economic Jessonism” – perhaps we might call it. This completely flew in the face on neo liberal conventional wisdom. I have absolutely no doubt that the remarkable success of the ARST between 1992 and 1995 was to have an important influence on the Labour-led government some ten years later.

Since that time the profits from the Port and other regional assets have been a key funder of Auckland transport and storm water projects – and are now virtually taken for granted in Auckland. It is hard to imagine how we could have embarked on the recent transport and other infrastructure upgrades without it.

The ARST had proved to be remarkably successful but ironically – not in the way it was designed for. For the New Right officials in Wellington it had been an embarrassing failure – therefore it had to go. In 1997, the officials went back to the drawing board and created Infrastructure Auckland (IA). This time there were to be no elected trustees. At the same time there was another attempt to sell off the regional assets by the National Government led by Jenny Shipley and Maurice Williamson – which once again ran into widespread public opposition and also from the Auckland mayors who had their own ideas about where the assets should go. But in a last gasp blow – the National Government recklessly forced the privatisation of the former ARC Yellow Bus company which was purchased by the Scottish company Stagecoach.

The name ‘Infrastructure Auckland’ was also quite revealing – because by the mid-90’s Auckland’s outdated infrastructure was beginning to reveal the consequences of years of neglect. First of all the drought of 1993-94 showed Auckland’s bulk water storage to be inadequate, the Mangere Wastewater Treatment Plant had reached capacity, and early in 1998 there was a major power outage in the CBD which was so bad it made international headlines. Bruce and I, Paul Walbran and Bruce Hucker anticipated these problems when we helped drew up the Alliance Greater Auckland Plan in 1995. Though the water, wastewater and power problems were eventually fixed by Watercare and the Auckland Energy Consumer Trust owned Vector respectively, the most deep-seated and intractable problem transport – grew increasingly serious with chronic traffic congestion and the city close to grid-lock. Chickens were coming home to roost after years of neglect by the state and by the region.

Interestingly in 1998 the regional assets were not handed back to the ARC but instead to the city councils. The councils were also gifted the shares of WaterCare.

In 2004 the political wheel turned once again and the Labour government returned the remaining IA assets including the 80 % shareholding in Ports of Auckland to the ARC, in the form of Auckland Regional Holdings. In 2005 proving the wheel had really turned, ARH bought back the 20% of shares in the Ports of Auckland which the Waikato Regional Council had privatised in 1993.

But in other respects Auckland was very much as Bruce Jesson described in his 1995 Accidental Politician article.

…Auckland remains a political mess, despite the local government reforms. There are four cities, three district councils, a regional council and now the trust. There is little cohesion at a regional level and constant squabbling among the politicians. The place is very much like a collection of medieval fiefdoms, from which the politicians ride forth to do battle with each other. Sometimes the cities were fine to deal with. Barry Curtis, the mayor of Manukau was always courteous and helpful. Sometimes they were difficult. Waitakere City councillors always seemed well meaning but obsessive. And Auckland City was invariably obnoxious.

It would be tempting to blame Les Mills, with his bombastic assertive style, for the arrogant tone of Auckland City, but that wouldn’t be fair. Arrogance is steeped in the culture of the place. The officers are as bad as the politicians. It dates back I suppose, to the days before local government reforms, when Auckland City regarded itself as the premier city in a region of tinpot borough councils. The intercity rivalries used to cause some embarrassing bickering at the mayoral forums. Les Mills would try to dominate proceedings. Barry Curtis would stand on his dignity and insist on the last word. Usually he would get it, but it sometimes took a long time.

The ongoing tensions between the city councils and the regional council surfaced once again in September 2006 when amidst widespread public protests at council rates increases, the Mayors of Auckland, Manukau, North Shore and Waitakere City were revealed to be planning what became known as the ‘Mayoral Coup’.

Though there was much talk at the time about a ‘super city’ – the Mayors actually advocated three cities and a ‘Lord Mayor’ and proposed that they themselves be appointed to the ARC as of right, along with ‘business leaders’ and even central government politicians and officials. They also called for the 2007 local body elections to be postponed. Essentially the ‘Mayoral Coup’ was an attempt to take control of the ARC assets and also to annex neighbouring councils Franklin, Papakura and Rodney. Waitakere, much to the indignation of its councillors, was also to be carved up. However the Mayors’ scheme was so transparently self-serving and essentially flaky that the whole scheme quickly collapsed amidst widespread public ridicule. In response the ARC proposed that the councils engage on ways to reform the Auckland local government system.

A formal process called ‘Strengthening Regional Governance’ involving all the councils was gotten underway with central government encouragement and a sort of consensus was cribbed together. The results were presented to the government which quite understandably was not especially impressed. In response it called for a Royal Commission on Auckland Local Governance clearly in the expectation of fundamental change.

In formulating the ARC submission to the Royal Commission we tried to keep in mind why there was Royal Commission in the first place – essentially this is because of widespread public dissatisfaction with local government in Auckland. There are I believe two principle reasons for this unpopularity – the cost of rates and user charges like water which in recent years have risen significantly higher than the CPI. The second reason is a perception of arrogance in the way local bodies deal with the public. I believe these two problems are to a large degree interrelated and probably relate to the corporate culture that is one of the most persistent legacies of the neo liberal colonisation of the public sector of the 80’s and 90’s.

Despite the assertions of the councils, in my opinion in recent years a far too greater slice of the rate-take is consumed in the administration of the councils themselves and on a whole network of contractors, consultants and consultancy houses. Furthermore a lot of these costs appear to be duplicated between the councils. As David Shand reported in his Local Government Rates inquiry of 2007, on present trends local government rates will become unaffordable to a large number of people – especially those on fixed incomes within 10 years.

As a result of the neo liberal influence, the old-fashioned ethic of public service and democratic accountability have been progressively weakened.

In formulating the ARC submission we were therefore confronted with a dilemma: How to achieve the regional cohesion and unity that many Aucklanders have been calling for, for over 100 years – genuine regionalism – but also at the same time how to retain and indeed restore genuine local government for local communities.

The ARC proposal for Auckland is radical but we believe this approach is the best way to deal with the persistent problems of fragmentation, rivalry and inefficiencies leading to the growing costs of local government. Essentially Auckland has outgrown socially and economically the present three-tier, eight council governance model. We believe it needs to be replaced by something much more efficient and cost-effective and indeed more democratic.

Therefore we are calling for the ARC and the other seven city and district councils to be abolished, to be replaced by a single Auckland unitary authority, which we suggest should be called the Greater Auckland Authority.

Essentially what we propose is in effect a single organisation but with two tiers of governance – what I would call ‘the One and the Many.’ A regional tier the Greater Auckland Authority – and a local tier comprising some 30 community councils.

Under this model all council assets and land would be owned in common by the unitary authority: local community councils would be responsible for defined local assets and activities and the GAA would be responsible for regional assets and projects.

The Greater Auckland Authority would be in charge of transport, bulkwater, wastewater and stormwater, waste management, heritage protection, RMA planning, regional amenities like the Museum, art gallery and zoo, the regional parks network, the volcanic cones. It would be responsible for a standardised building consent and a single rates bill. We envisage the Greater Auckland Authority would be administered by some 22 members elected from parliamentary seats including 2 or possibly 3 Maori seats,

On the other hand the Community Councils largely based on the present day community boards would provide local democracy, and be responsibility for local amenities, roads, parks and libraries. The Community Councils would have greater responsibilities and therefore greater standing in their community than the present community boards. The elected members of community councils would be called ‘councillor.’ Unlike the community boards, community councils would have their rights and responsibilities protected by statute.

Conversely, the community councils would be constrained from legally challenging the activities of the Greater Auckland Authority for some parochial purpose, – after all they would be members of the same unitary authority. In other words checks and balances would be essential.

Under the ‘One and the Many’ model there would be significant opportunities for close cooperation between the Greater Auckland Authority and community councils, for instance through joint committees and working parties.

Let’s be in no doubt that what the ARC has proposed to the Royal Commission is a very powerful governmental entity for Auckland. There would therefore need to be checks and balances between the regional and national levels of government just as with the regional and local level and a clear division of labour. But again one can see the opportunity for joint task force approaches between regional and central government agencies to tackle major infrastructural problems, similar to the way ARC, ARTA and Ontrack will be working on electrification of the Auckland rail network.

As I have pointed out Transport – or more to the point chronic traffic congestion has been a major problem for Auckland in recent decades. The good news is that after almost two decades of neglect the present Labour-led government has done a huge amount for transport infrastructure in Auckland and so has the ARC, ARTA and indeed the city councils. But the fact remains that in terms of rapid transit we still lag some 50 years behind Wellington – which is now embarking on a second generation of rail electrification – Why is this? Well the reasons are intimately tied up with Auckland’s political history.

As I noted earlier, the biggest infrastructural headache for Auckland up until the mid 1950s was sewage disposal. Transport – especially public transport was not a problem. Auckland had an excellent electric tram service supported by trains and harbour ferries. In terms of rail transport thanks to the research of Dr Chris Harris which was referred to in Chris Trotter’s recent book No Left Turn, we know that in 1947 the Ministry of Works had plans to electrify and comprehensively expand the Auckland suburban rail network in a similar way to Wellington.

The MOW plans remained on the books until 1954 at which time the Holland National Government in the form of the Minister of Transport, Railways, Works and Housing Stan Goosman managed to persuade the Auckland City Council to agree to their abandonment. Harris points out that the day after Auckland City Council agreed to effectively ditch the rail plans, the government signed the contract to build the Harbour Bridge – a cheaper than originally planned harbour bridge at that.

Harris argues that these decisions were conscious and deliberate and taken at the highest level of government to ensure Auckland was developed along a California/Texas American model – Trotter goes one step further and proposes that this was a form of social engineering. This may well have been the case for the result was an Auckland transport system, designed to give priority to the private automobile, and a city designed on motorways, shopping malls and sprawling suburbs and subdivisions – somewhat different to the more compact European style design of Wellington and Melbourne. And this is essentially what we have in Auckland today.

This scenario is strongly supported when one takes into account what happened to Auckland’s electric tramway – in other words light rail. The decision to end the tram service was taken soon after the rail decision and from 1956, 72km of tram tracks extending all over the isthmus were systematically ripped out at great cost – one must surmise the purpose was to ensure electric trams could never be economically restored. These decisions had a profound influence on Auckland’s future urban design and quality of life. A graphic illustration was the impact on public transport patronage. Up until 1956 when the population was just over 400,000 people public transport patronage in Auckland had exceeded 100 million passenger trips per year – after 1956 and the demise of the popular and convenient trams, patronage almost halved to around 57 million trips per year. From 1956 Auckland almost overnight went from having one of the best public transport systems to one of the worst. In 2008 with a population nearing 1.4 million people, Auckland’s public transport system, which is still largely dominated by buses, carries just over 54 million trips per year – at a cost of around $140m per year in public subsidies. The tramway in contrast, made a modest profit for the city.

Exactly how and why this decision was made is unclear – this part of Auckland’s history remains obscure and requires further research. One thing we do know is that at that time the Auckland City Council was still bitterly divided over the Browns Island sewage affair. Perhaps Dove-Meyer Robinson and his newly elected colleagues were distracted with the task of replacing the Browns Island scheme with the oxidation ponds at Mangere. Robbie certainly tried to make up for it some twenty years later but by then it was too late.

But then again its never too late – as Bruce Jesson pointed out in the last chapter of Only their Purpose is Mad. “There are no final victories in politics” – to which I might add and “no final defeats either.”

Today I am advised that this week the government is considering on an order-in-council allocating fuel levy funds to enable Auckland to begin what should have been achieved in the 1950s. So at long last we will be able to electrify the Auckland rail system, and embark on building the inner city loop, and hopefully extending rail to Auckland International Airport.

Auckland of course cannot complete these sorts of projects on its own – these projects are of national importance and therefore their success requires not only the support but the absolute commitment of the state. On this score the National Party’s position in regard to Auckland rail is a cause for concern.

Bruce Jesson was vitally concerned about Auckland and could be even said to have been, like Dove Meyer-Robinson, a saviour of Auckland – but he wasn’t just concerned about Auckland – and neither should we be. Bruce was concerned about New Zealand – he was a nationalist – a republican – all his adult life. The last article he wrote – just before he died was called ‘To Build a Nation’ which set out very optimistically his hopes and aspirations for New Zealand.

Bruce in his last years had become a firm admirer of Helen Clark. And Bruce’s confidence in Clark really is testament to his prescience because Helen Clark has grown over the years to become one of New Zealand’s most outstanding Prime Ministers. Had Bruce lived no doubt through his writing, he would have had an active and constructive influence on the fifth Labour government – or Labour led government. He would have generally agreed with and applauded the Cullen fiscal/economic approach – similar in many ways to that which he helped formulate for the ARST. He would have admired the logical progression and coherence (seen from hindsight at least) of the Cullen National Superannuation fund, Kiwisaver, Kiwibank (an Alliance initiative of course) and Kiwirail and the major investment in transport infrastructure. He would have also applauded the implications of these initiatives in terms of New Zealand economic nationalism.

He would have been critical though I imagine, of a lack of progress towards constitutional independence – in other words towards a republic. Bruce after all as Andrew Sharp has reminded us was not just a New Zealand nationalist, he was a New Zealand patriot.

The question of nationalism has always been controversial amongst the Left – and mostly the NZ Left has been suspicious or merely indifferent to it. There are of course arguments for this but Bruce rejected those arguments – and I believe he was quite right to do so. Many of the social problems we face today I believe comes from a lack of national direction and national self-belief. This lack of overall national direction affects the body politic, the public service and I believe the whole of society. The fact is the country has no overarching organising principle or idea – nowadays the national interest seems to limited to aspiring to economic prosperity – and for success on the sports field.

Whether people like it or not the vision of Empire was once the organising concept of New Zealand – George Grey was prepared to fight a civil war over it and New Zealand as a nation made huge sacrifices in blood and treasure in the two World Wars for it. But the British Empire is long gone. Nowadays – there would be a tendency to scoff at the very idea of the British Empire – especially amongst people like us. But despite this New Zealand still clings stubbornly to the vestiges of British Imperial rule. Whether or not we appreciate the essential absurdity of New Zealand’s Head of State living on the other side of the world – most people would agree that the British monarchy is increasingly irrelevant to this country. The disinclination of the Royal Family to send a representative to Sir Edmund Hilary’s funeral this year drew quite a lot of criticism – but in my opinion it was perfectly understandable. I think there was a subtle message being signalled from London (rather like the missives from London in the 1840s) – the new message from London is – that just as the Britain has come to terms with the ending of the British Empire then perhaps it is time that New Zealand did as well

New Zealand for its part seems to have become stuck in a pro-longed adolescence – living on the face of it a normal independent life but privately unable to bring itself to leave home. What I find interesting (and irritating to be frank) is the increasing tendency in recent years for bureaucrats and people in general to refer to the state, or the New Zealand Government as ‘the Crown’. I am not arguing here for a rejection of the British heritage – quite the contrary – but I think we need to apply our energies to create a new national vision to replace the vision of Empire – which gave our ancestors so much confidence and faith in their destiny. We no longer have that confidence and certainty in New Zealand and I believe we are a weaker society for it.

Before he died Bruce called for a new nation building exercise with republicanism as its focal point. For Bruce republicanism was not merely about making a nominal change to the head of state but and I quote “reviving and extending the concepts of citizenship and democracy…and combining the issues of national identity, egalitarianism and democracy.” For Bruce nation building was about “creating a cohesive society that can act internationally with some sense of purpose.”

What has this to do with the governance of Auckland – I believe quite a lot actually. There is a lot of talk about Auckland being New Zealand’s only ‘World Class City’, or being ‘World Class’ at this or that – but actually when you think about it – it is difficult to see how New Zealand can be ‘World Class’ let along Auckland, when New Zealand is not really a fully-fledged independent nation. In the day’s of Empire, within the living memory of many, Auckland was proudly known as the ‘Queen’s City’ – which was more than a mere catchy brand – it was an assertive political philosophical statement. But those days have gone and since that time in many respects in terms of its identity Auckland has lost its way.

Our city scape tends to reflect this loss of greater purpose. As we have become too much a dependent, derivative, international branch office economy, so our city has become jammed with cheap ugly buildings.

The city needs a new overarching vision – or organising principle. I am not talking about branding or marketing gimmicks which are about the business of attracting visitors and making money – they may have their purpose but are not about the cultural aspects of building a city society. As Bruce Jesson said in the last chapter of his last book “Nation-building is not about concocting an image of New Zealand for the benefit of the rest of the world. It is not a ‘branding exercise’…which is how some politicians treat it. Nation building is an internal matter, not an external one, for our benefit rather than the benefit of others.”

Our vision for Auckland should be of a city/region, which in terms of its built environment and quality of life aspires to match the sublime qualities of Auckland’s natural environment and for its people to have a unifying sense of purpose and national destiny. I would like Auckland to be known as the first city of the New Zealand Republic. I am sure Bruce Jesson would have agreed.

1 Response

[…] With his tweedy ‘Rumpole of the Bailey’ image Philip was a familiar figure around the corridors of what was then called Regional House and though the name of the organisation had been recently changed to ‘ARC’, I had joined what was in effect the last months of the old Auckland Regional Authority – the ARA. The place was filled with an interesting (and often discordant) mix of personalities – many of them household-name local politicians like Keith Hay, Lindo Fergusson, Colin Kay, Jean Sampson, Alan Brewster, Gary Taylor and many others. (See http://52.62.142.163/2008/10/strangers-in-the-21st-century/#more-27) […]