Stand for New Zealand! Kippenberger’s rallying cry at Galatas has message for modern New Zealanders

ANZAC Day Address by Auckland councillor Michael Lee on behalf of the Governing Body Auckland Council,

Civic Commemorative Service

Cenotaph, Auckland Museum and Domain.

Today we gather to solemnly remember the sacrifices of those who gave their lives for New Zealand in the great world conflicts of the 20th century.

On Anzac day we also take time to remember the dead of those other smaller conflicts – sadly ongoing – which Kipling called the ‘Savage Wars of Peace’.

ANZAC Day as we all know began as a commemoration of those who fought and died in the First World War – the Great War – and today is the 96th anniversary of the landings by Australian and New Zealand troops at a beach at Gallipoli – immortalised as Anzac Cove.

At the Anzac day parades when I was a boy I recall the marching of sizeable contingents of returned men who had fought in the Great War – the original Anzacs. As the years passed, they became progressively older and frailer, their ranks thinning, their numbers dwindling – until by the end of the 90s they were gone. But when I grew up also there were many thousands of returned servicemen and women from the Second World War – my parent’s generation.

Today I wish to focus on the achievements of that generation, the Second World War generation, – the generation described by American writer Stephen Ambrose as the Greatest Generation – while we are privileged to have the last of those men and women still amongst us.

New Zealanders can be justly proud of the huge national effort the country made during both World Wars of the 20th century. Its serviceman and women served with distinction on land, air and at sea. New Zealand’s casualty rates were proportionately one of the highest if the not the highest of any combatant nation. On the home front during the Second World War economic mobilisation meant New Zealand became a net donor of aid to Great Britain and the United States.

As with the New Zealand Infantry Division in the Great War, the NZ Division of the Second World War came to be considered by friends and enemies alike as an elite force. Indeed none other than Field-Marshal Erwin Rommell considered the NZ Division, the best in the British 8th Army.

But an elite force can only be forged after months, indeed years of training, with leadership, motivation and ésprit de corps – and also by the harsh testing lessons of combat.

In May 1941 the New Zealand Division alongside British, Australian and Greek forces, was ordered to defend the island of Crete from a German invasion.

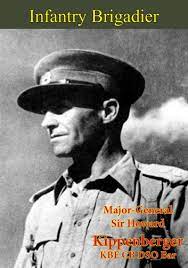

After days of bitter fighting, German paratroopers had seized control of the strategic Maleme airfield. In fighting around the nearby town of Galatas New Zealand forces came under prolonged heavy attack. Under the onslaught the exhausted riflemen of the 18th battalion began to fall back, the trickle of men turning into a stream. Had the line collapsed at that point, the enemy would have broken through and the whole position of the Allied forces on Crete would have been imperilled. The New Zealand Commander Lieutenant Colonel Howard Kippenberger (later Major General Kippenberger) moved amongst the retreating soldiers exhorting them to stand and hold – calling upon them to: “Stand for New Zealand! Stand every man who is a soldier! Stand for New Zealand!”

The average New Zealander is not inclined to be demonstrative, (especially in those days), nor do we tend to be hand-on-heart patriots – and this citizen’s army was no exception – but the evocation of New Zealand and everything that New Zealand stood for in the hearts of those men – rallied them. The retreat stopped – the line held. Indeed the next day, led by Kippenberger the New Zealanders counter-attacked and routed the surprised enemy out of the town of Galatas. This action saved the Allied position on Crete enabling most of the expeditionary force to conduct an orderly withdrawal across the mountains to be evacuated by the Royal Navy to Egypt. It was in the bitter fighting around Galatas that 2nd Lieutenant Charles Upham won the first of his two Victoria crosses.

The average New Zealander is not inclined to be demonstrative, (especially in those days), nor do we tend to be hand-on-heart patriots – and this citizen’s army was no exception – but the evocation of New Zealand and everything that New Zealand stood for in the hearts of those men – rallied them. The retreat stopped – the line held. Indeed the next day, led by Kippenberger the New Zealanders counter-attacked and routed the surprised enemy out of the town of Galatas. This action saved the Allied position on Crete enabling most of the expeditionary force to conduct an orderly withdrawal across the mountains to be evacuated by the Royal Navy to Egypt. It was in the bitter fighting around Galatas that 2nd Lieutenant Charles Upham won the first of his two Victoria crosses.

John Mulgan was one of this country’s outstanding young writers of the 1930s. Author of the depression-era classic ‘Man Alone’ he went on to Oxford University. Upon the outbreak of war in 1939 he immediately joined the British Army rising to the rank of Major and second in command of his regiment. The dashing Mulgan fought in the 8th Army at El Alamein and latter with special forces behind the lines in occupied Greece, winning the Military Cross.

Towards the end of the war he wrote in nostalgic terms about his memories of New Zealand from which he had been parted for many years.

Mulgan also wrote about his impressions of the NZ Division which he had encountered in North Africa:

“Afterwards, a long time afterwards, I met the New Zealanders again, in the desert below Ruweisat ridge, the summer of 1942. It was like coming home. They carried New Zealand with them across the sands of Libya. This was the division that had saved the campaign of 1941 at Sidi Rezegh. The next year, when Rommel came into Egypt, the same division drove down from Syria and up along the coast road against the tide of a retreating army to meet him, and waited for him near Mersah Matruh. They held there for three days. By the evening of the third day, the whole Afrika Korps, had lapped round them and was closing in. Ordered to come out, the New Zealanders attacked by night, led out their transport through the gaps they cleared, boarded it, and drove back to Alamein. Through all the days of a hot and panic-stricken July they fought Rommel to a standstill in a series of attacks along Ruweisat ridge. They helped save Egypt, and led the break through at Alamein to turn the war. “

“They were mature men, these New Zealanders of the desert, quiet and shrewd and sceptical. They had none of the tired patience of the Englishman, nor that automatic discipline that never questions orders to see if they make sense. Moving in a body, detached from their homeland, they remained quiet and aloof and self-contained. They had confidence in themselves, such as New Zealanders rarely have, knowing themselves as good as the best the world could bring against them, like a football team in a more deadly game, coherent, practical, successful. “

“It seemed to me, meeting them again, friends grown a little older, more self-assured, hearing again those soft, inflected voices, the repetitions of slow, drawling slang, that perhaps to have produced these men for this one time would be New Zealand’s destiny. Everything that was good from that small, remote country had gone into them – sunshine and strength, good sense, patience, the versatility of practical men. And they marched into history”

I close with some final thoughts by John Mulgan on the New Zealand he hoped would be created as an outcome of the sacrifices of the war.

“If the old world ends now with this war, as well it may, I have had visions and dreamed dreams of another New Zealand that might grow into the future on the foundations of the old. This country would have more people to share it. There would be hard-working peasants from Europe, craftsmen that love making things with their own hands, and all men who want the freedom that comes from an ordered, just community. There would be more children in the sands and sunshine, more small farms, gardens and cottages. Girls would wear bright dresses, men would talk quietly together. Few would be rich, none would be poor. They would fill the land and make it a nation. “

“In this country in a dreamed-of future, men will remember names of desert places that have been dignified by fighting, battle honours of a small country, of that New Zealand of the past, and they will share these things as part of a history that will be dear to them. ‘All earth has witnessed that they answered as befitted their ancestry; they endured as the strong influences about their youth taught them to endure’”

John Mulgan did not survive the war – haunted perhaps by demons from the guerrilla war in Greece, he took his own life in a hotel room in Cairo.

I think we New Zealanders in the 21st century, of my generation in particular, could take more time to meditate upon the sacrifices made by our ancestors, especially those of the World War 2 generation and to reflect upon the hopes and aspirations, the spirit of national unity and national purpose of New Zealanders of those times – and the high price for nationhood that they paid for all of us.

We need to ask ourselves have we measured up to those earlier war-generation New Zealanders? Have we managed well the great patrimony bequeathed to us? Have we honoured the unwritten covenant between ourselves and the dead.

In these uncertain, equivocal times the exhortations of Howard Kippenberger amid the noise and chaos of battle at Galatas call out to us – “Stand for New Zealand!”

Mike,

Many thanks for your support of the Passchendaele Society’s Commemoration Ceremony on 12 October 2011 at the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

In the third paragraph of your ANZAC Day address you say..”ANZAC Day began as a commemoration of those who fought and died in the First World War-The Great War”

In fact the first ANZAC Day ceremony on April 25th 1916 was a commemoration of the ANZAC landings at Gallipoli on 25th April 1915. Most of those who fought and died in the Great War fought and died after 25 April 1915. After Gallipoli the main force of New Zealanders were formed into an Infantry Division and sent to the Western Front where they performed as a Colonial Division of the British Expeditionary Force. There were no official commemorative dates set for the Battle of the Somme or the Battle of Passchendaele where the casualty figures greatly exceeded those at the Gallipoli landings.

This year the Honorable Judith Collins, Minister of Veterans’ Affairs set up a competition for year 13 students at all New Zealand Secondary Schools entitled “Why Don’t We Remember The Battle of Passchendaele?” and one of the reasons for that must be that the Government never gave the people the opportunity to commemorate the Battle of Passchendaele as it had done for the Gallipoli landings. For many New Zealanders therefore ANZAC Day is about the ANZACs and the Gallipoli landings.

The Western Front and Passchendaele deserves its own recognition and that is why the Passchendaele Society has been set up and why we will commemorate New Zealand’s darkest day on the 12th of October each year. Thank you again for your support.

Thanks Iain,

obviously Anzac Day 25th April commemorates the Gallipoli landings in 1915 – but this was in the ‘First World War – the Great War. As the years went on it soon became the day to commemorate all the dead of the Great War – until of course the Second World War and then all the wars after that. Though as my speech was about WW2 I was somewhat time limited to explain that in detail. Congratulations on your work to commemorate Passchendaele.

The 12 October ceremony was extremely successful. Thanks.